English-speaking is a daunting skillset.

This past Christmas, one of my Viet friends setting her new year resolutions as learning and practicing English better. She regretted that she did not pay attention to her English course in Viet Nam when she was studying college. She gained great scholarships from the university, but her English received negative reviews in the States.

Two years ago, I met a Viet friend falling into depressions as she thought the popular girl in her workspace ignored her because of her English-speaking skill. So every day after that, besides studying for class, she spent lots of times practicing for English pronunciations. She paid attention to the past tense and plural nouns, where the fluent English speakers artistically and effortlessly moved their tongues.

In my sophomore year in the States, I emailed a student service office to ask about tutoring positions. The staff responded quickly within a day, providing me with a lot of helpful information. I replied with an email asking for more details, and he followed up immediately. This new email ended up with the phase “Does that make sense?” It was my first time hearing the phrase and I asked myself “Does that mean my dialogues with him are the questions of the same thing and, thus, making him clarify the same info session again and again? Am I such an annoying foreign student?” I then responded with a short thank-you email and kept wondering if my ask was such a bothering to the staff. Years later, I learn that this phrase was commonly used in the American culture and media that at the end of the speaker’s part in a dialogue, they applied this phrase to check in with the others whether they were still paying attention to the speaker. I realized that in that email conversation, while I was not confident in my English skill, that staff might have not been confident in his explanation skills to the non-White student populations either.

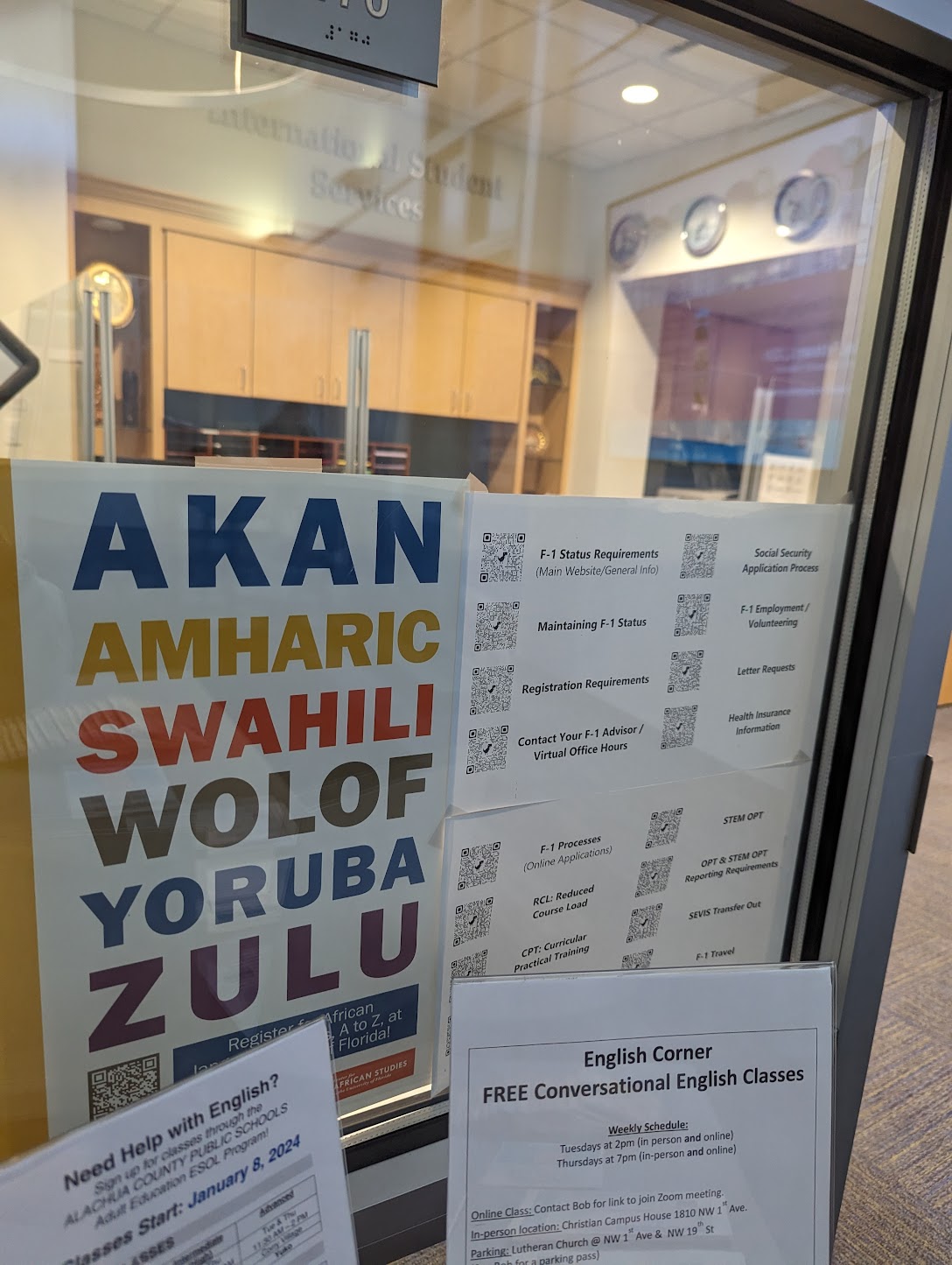

Many languages in the graphic promotions in the United States, in temple, school, and supermarket. Yet, the main language is American English.

Thus, English-speaking and -comprehending skills are among many factors that justify the English-speaking world as high culture.

In my freshman in the States, I was registering for a Psychology class as the gen-ed course. In the first few weeks of school, a Viet classmate sat next to me and asked, “Can you understand what she said?” On the lecture stage, the professor with short hair sat comfortably on the table, going through the lecture slides full of English words without looking at them. I responded in a questioning tone “Yeah, I do understand them well,” thinking whether I should adopt this guy as my friend. Later on, I remember spending hours memorizing the English phrases in the Psychology class without necessarily understanding them. I remembered the classic photo of the dog and the bell, Fight-or-flight phrase as it is commonly mentioned on the social media, and maybe nothing else. The newly adopted friend was right – I could hear the professors’ words but barely understood her. I avoided to say the truth because of the shame in unveiling my inferiority in language and, thus, culture. I did not want to admit being a foreigner to this space, where both of us shared. It was a mix feeling of embarrassment, jealousy, and hatred towards my friend, which I did not understand at the time.

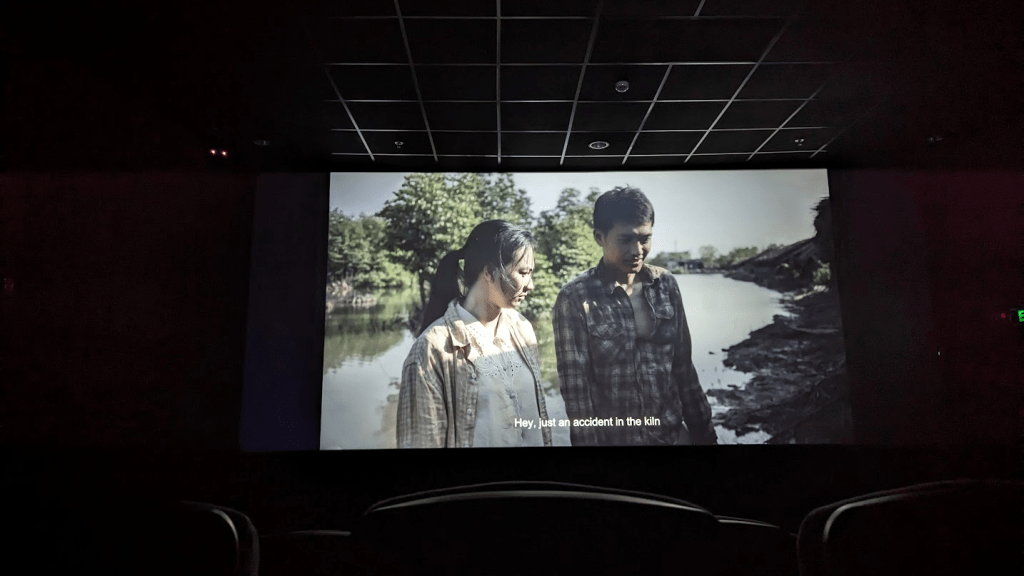

Another time, when our group of Việt friends planned to go to a movie theater and watch a popular movie at the time, another guy who studied and lived in the Midwest for almost a decade commented on us “Are you sure that you understand what the actors will say? There would be no subtitles as you could watch on the internet or Netflix?” We stared at him as if we could kill him. Most of our friend group just came to the United States. Although we had to take English standardized tests such as SAT/ACT/TOEFL/IELTS before coming here, our daily communication skills in English were still rough. We did not stay here long enough to pronounce the words well, and sometimes we zoned out when others speak in English with us. It was a slap to our faces who just wanted to adapt to the American culture and enjoy it in our own (foreign) ways. So, ignoring his blunt words, we brought a bunch of blankets into the theater – some followed through the movie until the After Credits while some were like me sleeping through the two thirds of the movie. He was so right that I was still deeply mad at him.

The same guy also suggested new Viet friends to relearn English communication skills when they had a chance to visit Viet Nam. Viet teachers will know Viet students better, so they could teach the necessary vocabularies and phrases to Viet foreigners easily. Because of this reason, there were many education centers in Ho Chi Minh city, Viet Nam dedicated for teaching English communication skills, besides the standardized tests. TED talks and movies in English are transcribed in Vietnamese and English for this reason, while several Viet teachers open Zoom classes for Vietnamese American to study basic English. The solutions for advancing English were there but we were busy with school, work, and entertainment as well as probably being blinded by the pride that we were already admitted as college students in the States. The guy’s words were tough, but I understand that he thinks about the solutions for the less-than – the beginners in the U.S.A. world, from the point of view of a teacher and long-term student who was familiar with racism towards foreigners in education.

Swallowing the emotions, non-English speakers inhabited English to survive in the globalized high cultures.

In the United States, there were at least 3 things to learn in order to survive: English, driving a car, and cooking the edibles. Firstly, the language to communicate with people, process through the paperwork which the States systems love dearly and be a part of the popular culture which is also dominated by English-speaking countries. Secondly, driving a car means to own a car and use them to various locations, because the States is a giant developed country, where all living equipment exist but are located far away from each other, separated by highways, cities, and even states. Thirdly, cooking the edibles so that when the foreigners can still cook our own food from the local ingredients in the States which are probably not authentic but partly soothe our homesick. The two latter skills can be replaced by affordable services such as Uber and Vietnamese restaurants, while the first skill – speaking English – has to be embodied in our tongues, ears, and brains. To learn English efficiently, almost all materials need to be communicated through this language, filling in the learner’s world and imposing in the learner and naturalizing the learner’s words. The success of this language probably means the learner think, speak, and write in this dominant language, and sometimes even forgot their mother-tongue language.

Through time, I’m gradually conquered by this language. So as those friends who were once beginners and, thus, commented by the honest guy. The friends in academics started to replace several Viet words with English words, or chêm Tiếng Anh, just because they are more conveniently produced from their bodies who effortlessly process through English in everyday life. Gradually, more Viet sentences are replaced by English sentences in discussions and arguments. I started to speak English to those Viet guys, taking this dominant foreign language for granted. Consuming lots of entertainment and educational materials in English, the senior Viet friends talk to the newbie Viet friends in English so they could practice English better. In a group of diverse friends, sometimes the Viet friends could not speak in Vietnamese as they might be deemed as unintentionally excluding other non-Viet friends in the conversations. When Vietnamese is a shared language of the minor group in an English-speaking space, English is suggested as a survival skill or a phenomenon of high-class by Vietnamese American. When Vietnamese in not a shared language of many people in the group, English becomes a common language, a common vehicle for shared interests of many people, and an expressive language of inclusion.

Even now, when you read these lines, you can see that my writing language is dominantly in English. I started living in Tennessee since I was 17 years old, making Viet friends as well as many people in diverse cultures in the English-speaking university space. When I live in Florida, I realized that befriending with non-Viet is as great as with Viet and, that way, English is overtly embedded in my everyday life. Among so many differences in culture, English is among a few common things between us. We shared joy in English, complained in English, cried and laughed after our long conversations in English. Through English, we asked each other about thank you, sorry, and I love you in our own languages. We started to pronounce our non-Viet, non-American friends with the native pronunciations and intonations, which we probably could not do in our own countries – the Global South countries.

Language is the embodiment of culture and politics of certain nation/region. Language is the vehicle of culture, through visual materials, digital media, and physical cultural artefacts. Language are delivered through words, facial expressions, body languages, the digital email, a TV show series, and a sport news. Through language and cultural materials, the dominant culture consumes the space, like how English has been used widely throughout the globe, in England, United States, India, China, Viet Nam, etc, internet, and now outside of the globe – the space stations. It is the language of the oppressor as their worlds expands beyond their physical fenced world. But does that mean the oppressed who speak the oppressor’s language will obey to the oppressor’s worldviews?

Knowing the language opens the doors of knowing the cultures, politics, and the people.

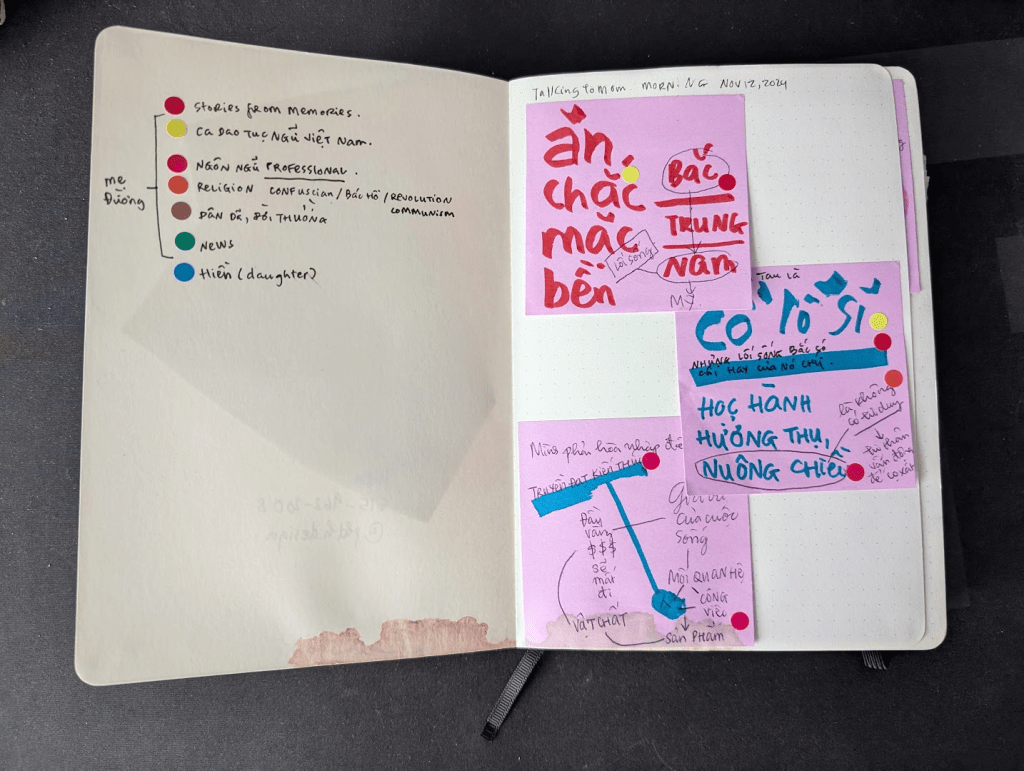

I still call my mom quite often. She only knows several classic words in English such as thank you, and often smiled with the English-speakers when they said something to her. Thus, my brother and I were usually her translators even in professional works. That allowed me to understand what my mom was doing and how I could support her with whatever I have. There were many things that when she spoke in Viet, her tones were much more straightforward and critical. Her language is richly embedded with Viet folk cultures whenever she tried to convince me to do something:

Cá không ăn muối cá ươn

Con cãi cha mẹ trăm đường con hư

The fish will be rotten without salt

The children will be naughty without parents’ words

or

Học ăn, học nói, học gói, học mở

You study every little thing in life: to eat, to talk, to wrap as well as to unwrap the gift.

Thus, when we talked through the phones, I did not only listen to how a Viet mom lives but also how the long history of Viet cultures is embedded in her everyday life and now delivered to her children through every possible conflict. Although the modern life is changing rapidly and some of her words could seem outdated, the connections to Viet language and folk cultures were what nails a Westernized modern soul to the essence of people, which is learning how to live and treat others properly and ethically.

At the end of the day, through the ups and downs of learning English and keeping up with Viet, I realized that learning the languages is the important note to understand the colonizer’s world and the colonized’s world. The understanding of both languages and cultures allowed critical comparison of both worlds and decision-making on alternative future buildings. That means, as a non-English speaker, non-White person, I possibly have access to more than one world in Vox or Fox News, through which the United Staters talk about other countries as if they were silenced. Rather, I could understand how the Viet perceives the heroic United Staters and the English-speaking worlds and other chances that we could do things differently. Plus, as many multicultural global companies settled in Viet Nam, they sought for people of diverse cultures and languages in operation. The use of language and cultural comprehension could be applied to critique the overemphasis of modern globalization as neocolonial strategies in the modern days.

In that case, I’m sorry for the United Stater friends that demanded the Viet folks to speak in English just because you have felt excluded. When you thought about the exclusion of language that we might have caused on you, you probably have not imagined the depressing moments that we learned your language as a part of our college entrance exams and had to analyze the grammar and word choices of every kind of conversations in English. While you spoke fluently in English, we lost our hair learning this foreign but globally dominant language. The inclusion in language and culture that you as English native speakers have taken for granted is actually the long-term result of non-English speakers’ labors and times.

The genuine, truthful inclusion is hard to execute in the English-speaking multicultural institutions with non-English speakers. Because non-English speakers have their mother languages and birthed cultures. The inclusion in the dominant narratives means appropriation and internalization of the dominant language and culture, which happens when non-English speakers think, write, and speak in English. Initially through forced homework in academics and gradually voluntarily and proudly as an icon of higher social class. The inclusion of dominant culture means we – the people to be included no longer see us as different from the dominant narratives. We are educated to think similarly but we still look and sound like a different classification due to our skins, eyes, hairs, and tones. The institutional inclusion of the diverse marginalized body means a forever classification of cultures: low cultures are the degradation of high cultures – the default icons of civilization. Accepting institutional inclusion as a marginalized body means accepting the displacement and alienation of self. It means a forever otherized embodiment that desires high cultures but is always perceived as low cultures.

Just as Fanon analyzed the colonized body with black skins in the desire of white masks.

Does this rage make sense?

My professors always asked why I was often filled with rage when speaking about cultural differences in a diverse group of friends. That is because I was among the folks who did not know much about the dominant language and culture. In a group of Viet friends, I started as among the youngest folks who did not know how to respond to the seniors without being critiqued as impolite. Thus, I always made mistakes and troubles in dealing with higher cultures. In a way, I was a part of the collective bodies who accompanied with low cultures that need to be appropriated by high cultures, always encountering with the phrases “you have to… because others know better” or “I don’t like that – it’s not appropriate.” I kid you not, these phrases are not only common in a traditional space like in Viet Nam but also in the space deemed as freedom like in the United States, signaling an imaginary mold of reproducing the aesthetics of certain high cultures.

In response to such phrases, I simply acted as a rebellious child, questioning out loud and even running away from such molds. When the molds are crafted with rationality that stabilizes high cultures, emotions of the people of low cultures, which are the immediate responses of human beings, are otherized, irrationalized, demonized, and eradicated. The rage takes place because its people are ignored, silenced, and misrepresented. In response to the questions from low cultures, of course, the people of high cultures often refused to answer. They barely know how to live with cultural differences but somehow, specifically in the United States, fall in love with the idea of being a part of the diverse collective (of minor ethnicities). Through so-called inclusivity, they proudly smiled for impactfully celebrating cultural diversity, while putting aside the deeply engraved pains of others as they already tried their best.

I put “somehow” in the comment of high cultures because I have observed their high cultures from a POV of the people of low cultures. They had the histories of settling and claiming the indigenous space as theirs with whatever highness in their language, technology, and religion. Although learning their language and understanding their words in their so-called space, I have no interest in rationalizing their behaviors or accepting their highness as the truth. I refused to perform the inclusivity that they have done even though they were not so critical of their actions. For now, when the anger still spreads through my lungs and questions still drum well in my ears, I’d rather observe the contradictions in their high cultures.

References:

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. In On being included. Duke University Press.

- Chaplin, C. (1936). Modern Times. United Artists.

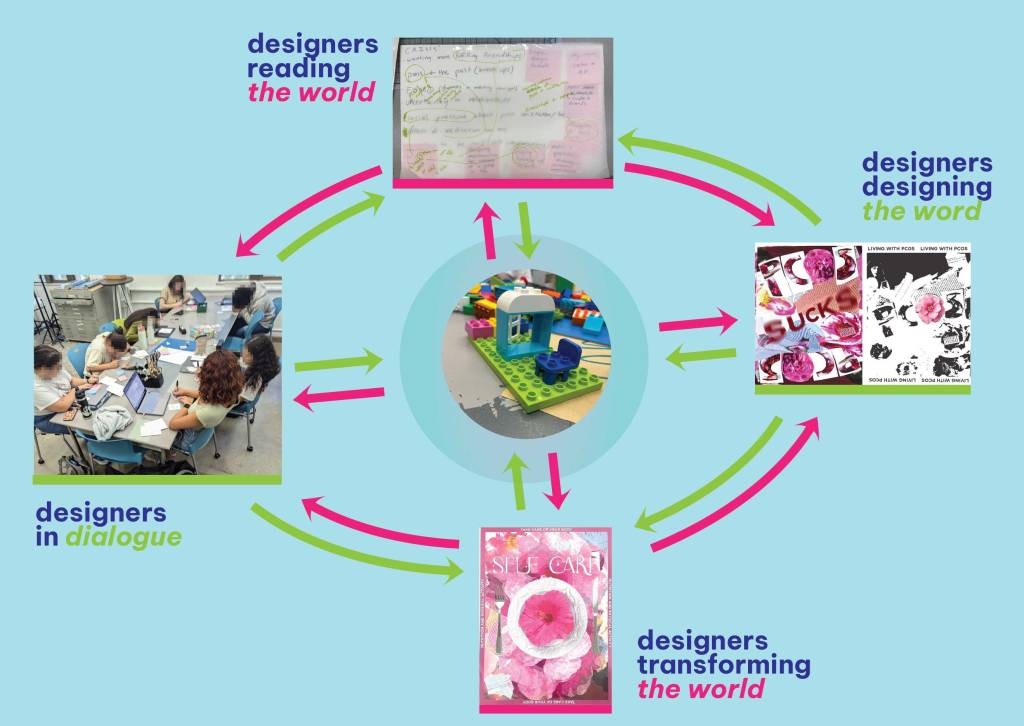

- van Amstel, Frederick. “Cultural Alienation in Design.” Frederick van Amstel, June 2024, fredvanamstel.com/blog/cultural-alienation-in-design.

Acknowledgements: I was watching Stephen Turban in Saigon Tếu, where the United States man was complemented and supported by the Viet for speaking Vietnamese in Viet Nam (?). This was when I realized the double standards, not only in sexism, but also in classism due to the use of languages by whom. This double standard made Turban shy in the show but, later on, he returned with English and his professional insights in several English-speaking Viet podcasts. Either way, to the Viet, any languages that the English-speaker chooses to use could be seen as the fabulous performances and demand giant applauses. Thus, I wrote this note to analyze a POV of non-English speaker in the English-speaking world. This could be seen as an amateur critique of Việt Nam sính ngoại, chêm Tiếng Anh, or the phenomena that the Viet loves languages, cultures, and products of the dominant cultures like the United States instead of theirs.