“You’re so low-tech!” That’s probably one of the common comments that I responded with our parents and grandparents in Vietnam. Along with my cousins and friends, I am a part of gen Z, being born and raised in the binary technological development of a postcolonial developing country. We had smartphones since middle schools while our parents transitioned from the Nokia with the phonebook as contact storage. Technology is developed and integrated in our lives exponentially, making the people with little or lack of knowledge in using, dealing, and manipulating technological devices become categorized and labelled as old-er, slow-er, less-than, or “low”. The experts in high-tech are deemed knowledgeable and the high station for the lows to visit and ask for knowledge. Even when the old population tries to catch up with the young generations on these technical programs, they might not perform these hard skills as well as the young ones.

Similarly, when a graphic designer talking to computer science teams, they often looked down on designerly approached in UXUI, thinking that graphic designers generally offered a “dramatic” inefficient skin to programming without actually understanding how programming, coding, big data, efficiency, accessibility, and ethics work. In a way, graphic designers were deemed irrelevant when trying to step our foot in contributing to technology, with our expertise in interactive, visual design. Our efforts in producing UXUI, visual design, and web design, thus, seemed irrelevant to the CS occupations. Why? I’m still trying to understand this occupational privilege in technology. I read Dr. van Amstel’s blog on transdisciplinary design, through which I understand that (graphic) designers are undermined by CS engineers probably because of our generally transdisciplinary approach and, thus, collective positionality and action as users of the high-tech design platforms.

My commitment to low-tech design is partly due to this look down by the OG technical folks, who venerated the accuracy, efficiency, and protocols in their profession as if they were the only ways life should be made of. By emphasizing on such technical worldview, creativity and tactile knowledge is thrown outside of the window before being put on the table. This anti-dialogical approach of high-tech designers (or developers/programmers/engineers) towards other is, surprisingly, normalized in collaborative conversations. Low-tech designers are often refered to owning art projects that consumed technical space, slowing down the efficiency in data storage and looking quite messy in comparison to the modern, high-tech aesthetics. This binary assumption segregates low- from high-tech, restricting opportunities of growth for transdisciplinary designers, and silencing democratic, ethical knoweldge and practice of technology. That’s probably why several graphic designers are afraid of the genAI emergence, as well as the rise of anti-intellectual yet efficiency-loving wave.

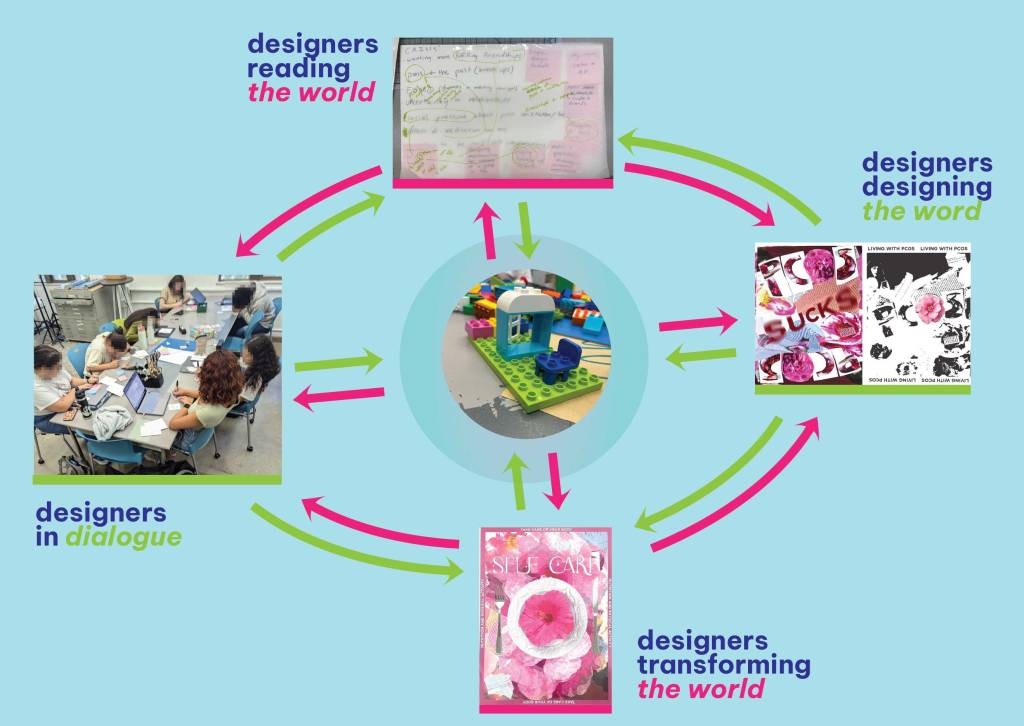

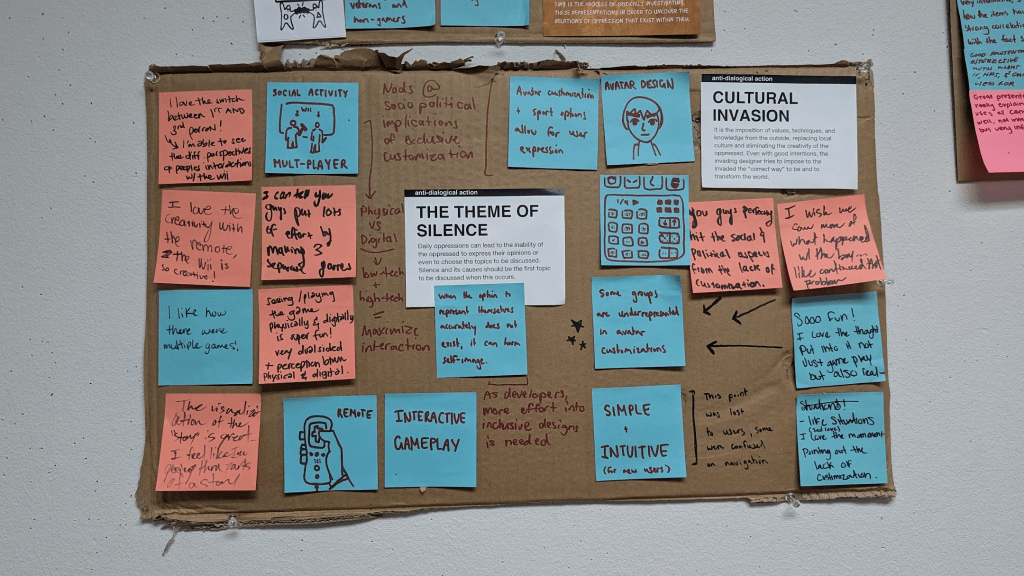

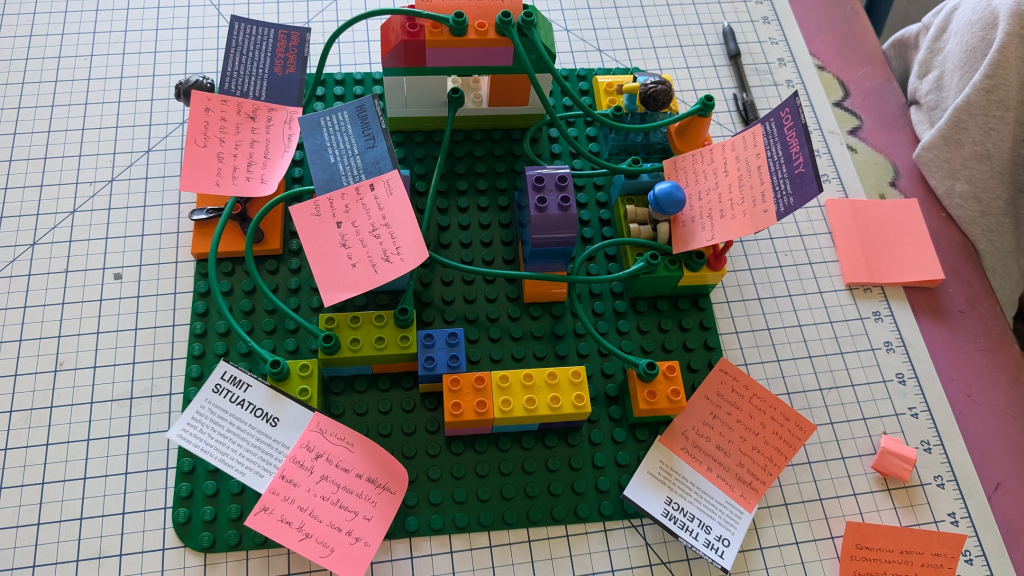

As a part of the Design Technology course, spring 2025, we have researched on the existence of low-tech design objects as the contribution of non-designers and designers who our classes transitioned to the critical understanding of high-tech through acting many roles towards design object: from regular user, super user, to developer/designer. Through many levels of interacting, observing, analyzing, and reimagining with the design objects, students participated in interaction design through theatrical approaches. This is inspired from my interest in Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed and Rainbow of Desires, introduced by Dr. Frederick van Amstel, one of the pioneers in researching userism as a critical, liberative design research in Latin America.

This theatrical approach in interaction design emphasizes the immersive, expansive role of high-tech objects, when students already researched about the roles of low-tech design objects in everyday contexts. Several low-tech design objects that students have researched included gum, magazine, ink, printer, pencil, and mood board. They are often physical materials, which forms are adjustable, distortable, and elevated with other design artefacts (ie. pencil could be customized through artistic craft of typography). These low-tech design objects can be transformed through digital platform for convenience in data storage and (international) collaborations. Low-tech design objects can be redesigned, distorted, and repurposed easily as the design body understands these objects through tactile knowledge.

Meanwhile, high-tech design object can be understood as meta-object, which allows many rooms for exploration, dialogues, and critiques. However, these allowance are often dismissed due to the reduction of high-tech design object merely to its efficiency, entertainment, and technical excellence. Thus, users have been ignored to emphasize eurocentric approaches in highlighting colonial aethetics and functionality.

To delimit the dismissal in our class, the viewpoints of regular users and super users are emphasized in our class, exploring and practicing the cloning process of high-tech. Through researching the high-tech platform and embedding their viewpoints, struggles, and alter/native thinking, students challenged the promise of high-tech in importing efficiency. Students realized that the high-tech design objects, including Instagram, have designed their behaviors, habits, and ways of communications. This platform specifically shaped the younger generations, who keep in touch, collaborate, hang out, and consume digital entertainments through an accessible, inclusive high-tech platforms. Very pluriversal with many-in-one – the signature combos in USA fast service design.

Through many theatrical roles towards high-tech, students reflected on themselves as designers, super users, and regular users of the cloned high-tech platform. In comparison to low-tech, high-tech earns a big selling point. Through the big database, high-tech has made its structure more accessible to a diverse user populations, including many scenarios for the users to customize their digital profile, strategizing their digital gamification, and planning for digital victories. High-tech platforms included many rewards of futuristic, achievable possibilities which aesthetics and impacts are, meanwhile, lost through low-tech materials. The cinematic, storytelling impacts of high-tech are pungent, creating immersive scenarios where prospective users to participate and imagine worldviews within. Meanwhile, with low-tech materials as the simple, distortable, monstrous aesthetics (Angelon & van Amstel, 2021), each designers are often asked to think and make their designs alternatively. Bluntly speaking, low-tech materials are so out/beyond the colonial, standardized aesthetics that graphic designers often give up on. In this case, aesthetics in design became the pressure that designers are scared not to think alter/natively.

Students analyzed high-tech through cloning, customization, and integration of low-tech, Makey Makey, and Scratch.

Physically in the USA and digitally in Vietnam, I found the differences in reactions towards the rise of AI and ultra tech, in the education sector. While there is a rise of anti-AI in the USA education, in support of anti-imperialism critical strands, educational population in Vietnam is highly susceptible towards this technological changes. With the collective cultures that we often embody and perpetuate, even sometimes obsessively, organizational cultures and governments are opened to the technological impacts from the worldwide empires (ie. USA and China). The digital turn of technology was abrupt to us since the 2010s, forcing the old population to adapt to this technology as if it was the only way to connect to the big world, new media, and the young generation. This social movement asks for openness in the low-tech folks as well as the patience and support from the high-tech ones. Even there are tensions among these binaries, the collective cultures forced us all to move forward, although I’m not sure if this forwardness is sustainable to Vietnam geopolitics. During this process, social hierachies remain due to the long history and culture of Vietnam as a small, autonomous, yet flexible nation.

Coming back to the education sector in the USA, I often felt isolated as a student and teacher. Not sure if that is because I am a minority or because of the different urban settings and institutional development of this space. Anyhow, I observe many reactions towards the impulsion of genAI in the student body in Florida, USA. With the dramatic entrance of genAI, of course, our worlds are shaken, as digital materials are one of our dominant source of consuming and creating cultures. It is the new norm in such a multicultural, yet highly industrial world. It could be hard for the young generations, of course including me, to imagine the alter/native or the ethical futures of this genAI chaos, when artist and research intellectual contributions are attracted to the big database for machine learning and language processing. Our worlds were started when the digital era was taken as the default of the supreme developments of USA empire. The more immersive high-tech is designed, the more meticulously we are designed as users.

Several students suggested touching grass when the digital eras are overwhelming. Despite this quick comment, their suggestions uphold a possibility of the physicality of human touch, use, and design. Understanding that users of high-tech are often undermined, the users’ database was actually where the high-tech platform is sprouted from, developed, excelled, and affirmed by. Users are attracted, analyzed, and manipulated without knowing (ie. Facebook and Apple sold users’ private data). Following the traditional approaches of Latin American designers and educators in low-tech design and decolonization history, the co-existence and transcending development of all-level-of-tech is highly considered and to be developed further.

To whatever kinds of tech, maybe users would counter-attack the judgement “You’re so low-tech!” by hijacking into the high-tech meta-design space. Users would be angry enough to mask our democratic interest with luxurious high-tech design, in order to intervene and design the high-tech alter/natively. Or maybe users end up not needing high-tech at all, and we still claim our epistemic position to democratically contribute to the technological chaos.

Acknowledgement: This blog is a reflection on the Design Technology course, Spring 2025, University of Florida. I have been supported by Dr. Frederick van Amstel and the student body during this dialogical approach in guiding this course.

References:

- Angelon, R., & van Amstel, F. (2021). Monster aesthetics as an expression of decolonizing the design body. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 20(1), 83-102.

- Ewenstein, B., & Whyte, J. (2009). Knowledge practices in design: the role of visual representations as ‘epistemic objects’. Organization Studies, 30(1), 07-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840608083014

- Filip, Diane & Lindegaard, Hanne. (2018). Filip & Lindegaard (2016) Designing the Object Game. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324865935_Filip_Lindegaard_2016_Designing_the_Object_Game

- Gonzatto, R. F., & Van Amstel, F. M. (2022). User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74(5), 758-781.

- Mazzarotto, M., & Serpa, B. O. (2022). (anti) dialogical reflection cards: Politicizing design education through Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy.

- Mørch, A. I. (2011). Evolutionary application development: Tools to make tools and boundary crossing. Reframing humans in information systems development, 151-171. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-84996-347-3_9

- Van Amstel, F. M. (2023). Decolonizing design research. In The Routledge companion to design research (pp. 64-74). Routledge.

- Van Amstel, F. M., & Gonzatto, R. F. (2020). The anthropophagic studio: Towards a critical pedagogy for interaction design. Digital Creativity, 31(4), 259-283.