When Ae-sun lost her child, Gwan-sik dropped his body at the seashore. Geom-Myeong cried when her dad ensured her that he would be there, with her, as always, even when she was married. The ocean has always been a part of their lives, just like how tears have followed them through ups and downs. The small village near the ocean has kidnapped some children and adults away, but they could not hate the ocean too long. Because they had to make a living from the ocean, the nature, the jungle whom they could not understand, until their children could be admitted to the big universities and altogether departed from the harsh nature. That made me realized that my childhood has been filled with the cinematic tears, separating itself from my homework and family.

Whenever I heard of a Japanese or South Korean nearby, I often wanted to see their faces, pronounce their names, and share my knowing of their cultures and languages with them. As if it was time for me to conduct a 15-minute impromptu language exam. Just like how I initially got to know a United Stater or English-speaker, I often got to know Japan and South Korea as a culture through media and music before I know the people in person. How to say, getting to know them is like watching Disney’s Frozen for years and eventually seeing snow for the first time. To a (grand)daughter of fishermen and military family, seeing new horizons of embodied cultures through my eyes and hands was like stepping through the Doraemon magic door and detecting the world with Conan.

A childhood soothed with multiculturalism

On the very first days of adapting to a new “life” of VAS in the 3rd grade, a classmate mentioned that she binged watch through the nearest episode of Boys Over Flowers, where the beautiful men were starred with the most romantic (shared) love. Through this class, I knew about High School Musical as parts of the English cultural class, learning the movies as if they were the method to excel English. Since then, I carried the language myself, as my grandpa could not teach me the language of the opposite side. My brother still struggled in adapting to the Western culture and language himself in his middle school. Meanwhile, like a sponge that was barely soaked with either Vietnamese or any other languages yet, I started speaking English as my second language as an 8-year-old.

The English culture in those years was different from my first grade in public school Thạnh Mỹ Tây, where I learned English in a class of around 40 people, repeating the phrases “I’m fine, thank you. And you?” multiple times in response to the cultural greeting “How are you?”. The English class was always at the end of the day, when I always wanted to go out of the school, waiting for mom in tears, often in the rainy days. The days in that public school were always long, crowded, and moist with the smell of nearby live market and dark chanel. I was always one of the last kids to be picked up.

In VAS, I remained one of the last kids to be picked up, still, but the school was always filled with lights. The glass walls allowed me to see through the officers on the first floor. My name was called out and greeted dearly by the security staff, as if they knew my mom, my uncle, or whoever in my family in the Ford Everest. The waiting time was no longer gloomy, since we had a big TV in the air conditioned, big ground, broadcasting Disney channel with Phineas and Ferb, Mr. Bean, and whatever there. The shows were lively and colorful, with Vietnamese subtitles, and I could sing along the catchy intro songs without the need of understanding them. Just like that, I was picked up by the Ford, driven by my uncles, where we sat comfortably through the rains and traffic jams, while scooters around us struggled. It was like looking at my mom, my brother, and I in the thick rainsuits where we pushed her scooter through the evening flood. This scenario returned when I left the VAS.

Until then, English phonetics became a course and attention from a Western teacher became a reward. I started paying attention to the end sound r, s, z, and how “Good Job” or “Excellent” with smiley faces as the grades instead of the numerals 9.25 or 8. That’s probably has crafted a default smiley face on me, even until today. Those few years of private school has Westernized my worldview without my knowing, passing through the window as quickly as my mom’s feminist career. Since then, my speaking skill in English was probably naturalized, or maybe I was more susceptible towards new cultures. Now that I realized, as a child, being opened to foreign cultures could mean a turn-away from home, especially when our families and cultures depend on the luxurious foreign school, culture, and businesses.

After that, I joined Lê Quý Đôn, probably where middle class kids went to. However, we spoke Vietnamese as usual. I learned Japanese as my second language, forgetting the naturalized English. I could sing along foreign cultures without understanding their languages, such as Westlife. I learned South Korean culture through my friends in middle school, where Girls’ Generation, Big Bang, and Super Junior became the idols in everyday life. We could hate each other just because we followed different girl’s band or boy’s band. Just like that, as we opened our bodies to sing along, dance along, and go along the cultures, we idolized the stars more than anything. The commune song “Dear my family” could make me cry. My cousin and I would print the Romanized lyrics of the South Korean songs so that we could remember through repeating. This repetition of language was like Karaoke, passionately and collectively, as if our hearts were carved with the foreign lyrics. Eventually, we leaned on the foreign language, culture, and aesthetics as the standard of our future self-representations, normalizing the imposter syndromes.

A return away from multiculturalism? Or a different understanding of it?

Ever since I started my MFA/MxD thesis research, I was scared of looking back to what I have done culturally. The coloniality in making of the Japanese, South Korean, and United States’ media and music was a childhood backdrop to me. They carried me through the gloomy and lonely days of family troubles, where coloniality is embedded differently in the adults. Through digital access to the cultural imperialism, I attempted to cover my ancestor’s financial and mental poverty, with the aesthetics of the foreign media. There, even loneliness, breakups, divorces are treasured as the artistic marks. Here, in my ancestors’ lives and shadows, they are hidden as crimes, regretful tattoos, rebellious hairstyles to be dismissed, and a broken glass to be replaced. Here, life is too sad and poor not to cover, fix, or move on. Here, sadness is a struggle of hungry stomach, sun-burnt faces, and belly fat from long days of sitting in the office and scooters, rather than a cinematically safe, artistic shelter to refuge at, without the pressure of time. There, a lover would return, a hero would pop out with the savior toolkit, and karma would be returned in a foreseeable gift of equity. Here, sadness is covered, distorted, and incarnated as sarcastic happiness, determined disappointment, and shaky steps towards the light. Even that means there would be lots of dead bugs around the streetlight in the morning. Here, our time and sadness could be traded with tuitions and school lunches of my mom’s children, if she learned to run through silence.

Because of so much embedded sadness, I intended to seek happy ending for any movies that I could watch. Or maybe happy endings are made as defaults of commodified cultural promises in Disney, Ghibli, and Hallyu not to shatter any children’s hearts. Maybe that is how coloniality is masked by the happy promises, where the sadness of poverty, unemployment, and struggling parenthood of the colonized are somehow solved just be the dreams of children to complete lives alternatively. This alternative means alter-colonized, implying the savior role of the colonizer. Coloniality is embedded in my lessons of cultures probably because of the determined happy endings of the protagonists, regardless of their struggles. I didn’t know that this happiness would forever set ground for the imperialist, colonizer, just like the otherization of Vietnam below in the USA.

Maybe my grandparents were scared of shattering my artificial happiness, or maybe they have been grown with the dream of such thrilling, detective, and eventually just movies. They seemed to enjoy such dupe eventful, adventurous lives through media entertainments, such as Bao Zheng and the Journey to the West. On the night my mom went home late, she brought bags of bòng bong to us, while we were watching the talented yet gentle Han Ji-min in Lee San, Wind of the Palace. Besides the baby steps of their grandchildren and their boastful careers of their children, their comments, nods, and laughter gradually filled the little corner of their house. Just like Mom and anh Thuận, I barely saw them crying. Until my grandma argued with Mom and wanted to go to her birthplace. Until my youngest uncle passed away.

Or maybe my grandparents struggled to grow their modernized, Westernized, and loosened grandchildren where other than the old stories and places, they did not know what to tell or where to go. They were left behind, just like how the anti-colonial struggles of Vietnam was then neglected or hindered through the foreign cultures. Or the histories of Vietnam were neglected until this country could become wealthier and more powerful geopolitically to speak for itself. Thus, it shook hands even with the imperial countries that it has fought against.

Neoliberal multiculturalism as a vehicle for the marginalized?

Just like that, I was suggested to research about Vietnam or Asianness in the United States, because they have resources for me to do so. Or because I was drawn to the fetish of this identity that I often did not have. My life when researching about Asianness/Vietnam was split, as the generational struggles remain in Vietnam while Vietnamese American generally celebrated their lives aesthetically, financially, and kindly in the USA. I realized that aesthetics was artificially and automatically generated as long as the designer and writer stays in the USA and is guaranteed with the USA neoliberal multicultural norms. In a while, I forgot about my childhood where my family is always a part of, splitting the picture to the sunny gloom and the gloomy sun. In a while, I learned to celebrate the Vietnamese and Asian cultures as how the neoliberals learned to do to protect themselves against the dominant narratives, together crafting the reality of American dream.

Just like that, I learned to love the Hollywood, Disney, Ghibli, and Hallyu cultures, even though they intervened the Vietnam territory and history in many ways. I learned years of the imperial language Japanese and mimicked Korean as my hidden talents, which would be found as an embarrassment of a Hallyu cultural fan. Through Little Women, the South Korean veterans seemed to be proud of the Vietnam war that they contributed to. Through the Green Dragon, the Vietnamese was elite, small, and helpless. I loved Joe Hisaishi and Haraki Murakami, not thinking that they described the postimperial lives as aesthetics of innovative solitude.

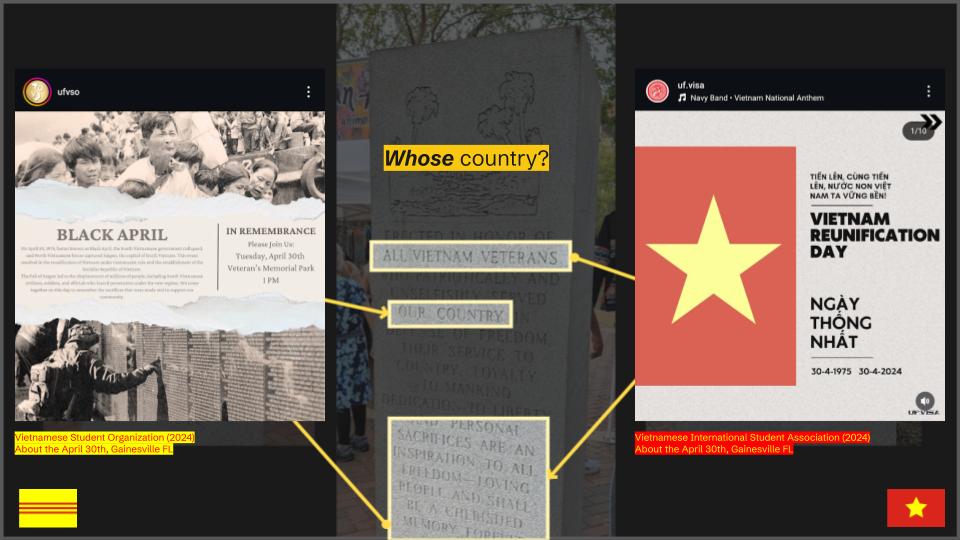

Somehow, when the South Korean turned towards their history, I was shaken and asked to turn towards my ancestors. When Ae-sun lied on the cemented road to refrain the Olympian USA whatsoever to enter Jeju and adjusted the local business, somehow it meant a resistance towards the hero USA itself. When the poor civilians covered the death of Ae-sin’s enslaved person to protect the noble from being captured by the Japanese or USA, I realized the community is the little hope of nationalism when feudalist elitism and government was beaten by the Western/European colonization. South Korean is one of the cultural imperialisms that has deeply impacted on me, showing the parallels in history between Vietnam and Korea in front of interventions. One of many things that made these countries different from each other is that one is split, enriched, and developed, while another found its ways as a developing whole. Now that Vietnam is in thriving developments and Vietnamese American gradually occupy spaces in the USA literature of minorities, there have been many ways of rewriting the history aesthetically, even that means bias and fetish in tear, joy, and doubt – all for justice of the marginalized.

As always, my childhood is like a little pond, where my ancestors mirrored themselves through sunny days and rainy days, on the side just like a big tree where the Buddha sat near the ground at. That’s how my mom often wished my grandparents an eventful and healthy upcoming year, every time we celebrated their new ages. The old but respectable ages. Besides mom’s celebration of her parents, there was always sadness, disappointment, loneliness, or tủi thân in her, who is an oldest daughter of the Confucianist semi-elite northern Vietnamese family. Tủi thân means sympathy for self because of the lack of sympathy from the others, like a mental self-hug since the language of neoliberalism as a part of individualist capitalism wasn’t there to secure and lift her up yet.

At the time I wrote this blog, I have been pondering on When Life Gives You a Tangerine while listening to:

- Tình ca

- CÁNH THIỆP ĐẦU XUÂN | TUYẾT PHƯỢNG x LÊ NHẬT OITA | Cha đàn con hát (cover)

- [Music Clip] IU(아이유) _ Neoui uimi(너의 의미) : Meaning of you (Feat. Kim Chang-Wan(김창완))

- [4K] D.O. (도경수) & IU (아이유) – Love Wins All | IU’s Palette (아이유의 팔레트)

- Hello Vietnam – Beo Dat May Troi at Suntory Hall

- [4K] IU (아이유) – Aloha (아로하) + I Like You (좋아좋아) | IU’s Palette (아이유의 팔레트)