Questioning the norm

In my second year in graduate school, I was pondering about my design research for thesis project. I was not so interested in designing new products or services as they were abundant in the United States market. However, the people remain unfulfilled with this wealth of product and service development. Every year, high-tech products were massively manufactured, advertised, consumed, and wasted. As prospective users’ budget is limited, they leaned on the guidance of Youtube product reviewers who are sponsored by the product manufacturer and provide “legit” reviews on the sponsored products. As the reviewers commented on the products, the prospective users measured their choices, creating a network of users that shared the material-based ideology of the branded products and sponsored reviewers. Teenagers could desperately love Apple products and the network because their friends participated in the ideology of sleek, modern, fashionable Apple products from the United States corporation. Thus, Apple product is expensive not only because of its design in forms and functions, but also because of the “vibe” and identifications of the prospective users that this product could deliver.

In response to the design monopolies with categorical aesthetic and functional products, young designers feel pressure to conform their design practices to the contemporary standards of the product market. I was in that position as well, pressuring myself and my practice to be hirable, recognizable, and massively manufacturable. The desire in designing, thus, is already standardized by the aesthetic sensibility from my experience as users. The freedom in designing, thus, is already conditioned by industrialization and consumerism.

What graphic design undergraduate students learn in the United States is a reductionist simulation of the industrial design process, which allowed them to understand the design process as a manufacturing assembly. This simulation satisfies the graphic design students’ desire of entering the industrial workforce yet risked not training students to think critically. Students, thus, felt successful from academic performance because they know what industrial designers should know. When students are asked to challenge or think beyond the industrial designers’ standard knowledge, they could be frustrated. Thinking beyond designers’ knowledge means being critical of the designers’ knowledge as a part of the industrial manufacture and, thus, siding with the users’ knowledge. Thinking beyond designers’ knowledge means siding with the users’ knowledge. That means a step closer to challenging the designers’ prestigious profiles. In that case, who would want to be critiqued and denied?

But, the designers’ self-critique and other-critique is needed. Because designers are among the main labor forces in producing products and, thus, wastes. Yet, we are often detached or blinded by the product wastes because we already labelled ourselves in synonyms with sleek, modern, fashionable designs. I saw my graphic design students’ pride yet lack design consciousness of their works. Seeing them was like seeing my old self – lots of hope, pride, and naivety through my privileged design skillset.

A commitment for alternative in design education

I was introduced to design consciousness by Dr. Frederick van Amstel, who then guided my studio-mates and I to critical pedagogy in design education:

Design consciousness is a theory + practice of assembling collective design bodies from participatory design activities and shared design spaces.

Dr. Frederick M.C. van Amstel, 2023

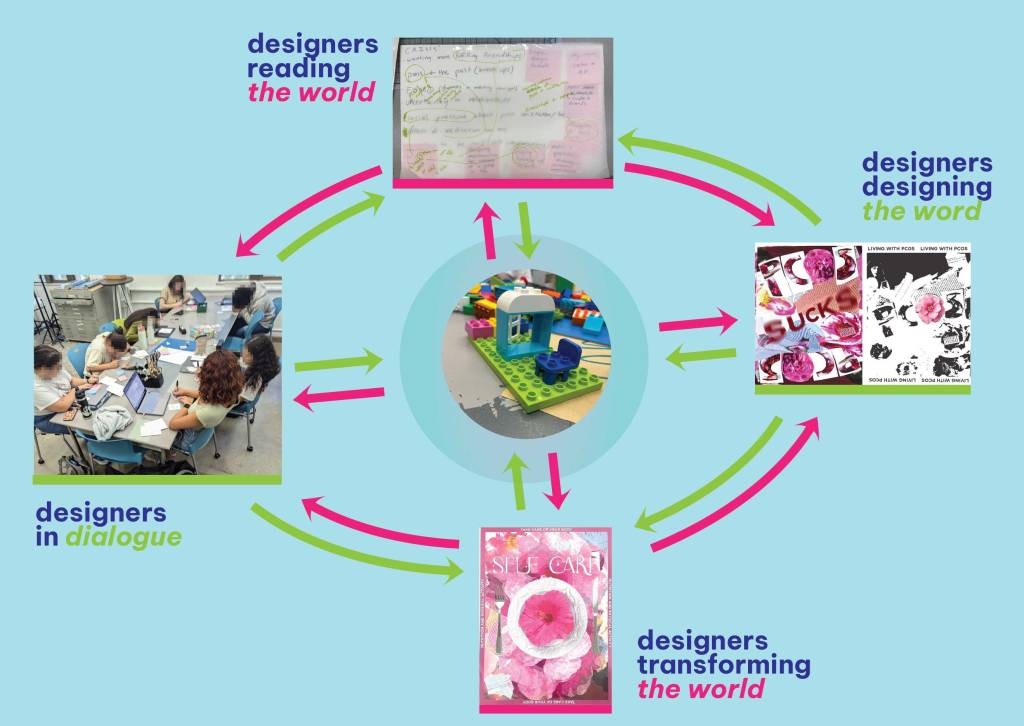

It was a new road in decolonizing design research and education that I sought hope from. Design consciousness allowed me to understand the handiness cycle of design object and body, through which designers and users are responsible for all changing phases of the design objects. While applying the pursuit of design consciousness in my MFA thesis practice, I also integrated this theory in my teaching of undergraduate design courses.

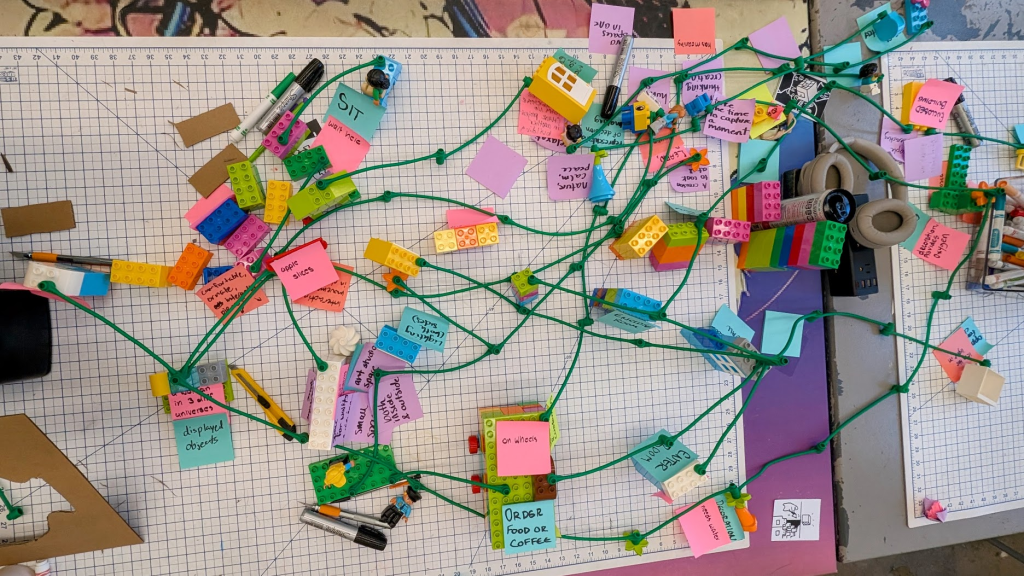

In a Design Technology class, graphic design students often expected to excel design skillsets in certain programs such as Adobe. However, I approached alternative meanings of design technology, which is the make tool for any design body to express their thoughts, emotions, and intentions. Students then used Lego Serious Play to recreate the design space that they were frequented at. Students then analyzed the design objects through describing their forms and functions. Students then created a network of design objects based on the descriptions, allowing them to alleviate themselves from certain brands of the design objects (products). Students described the institutional space, where they went to school, worked on assignments, starved, and also gathered with friends. Most of the time, students surrounded themselves with low-tech materials and natural resources such as light and plant.

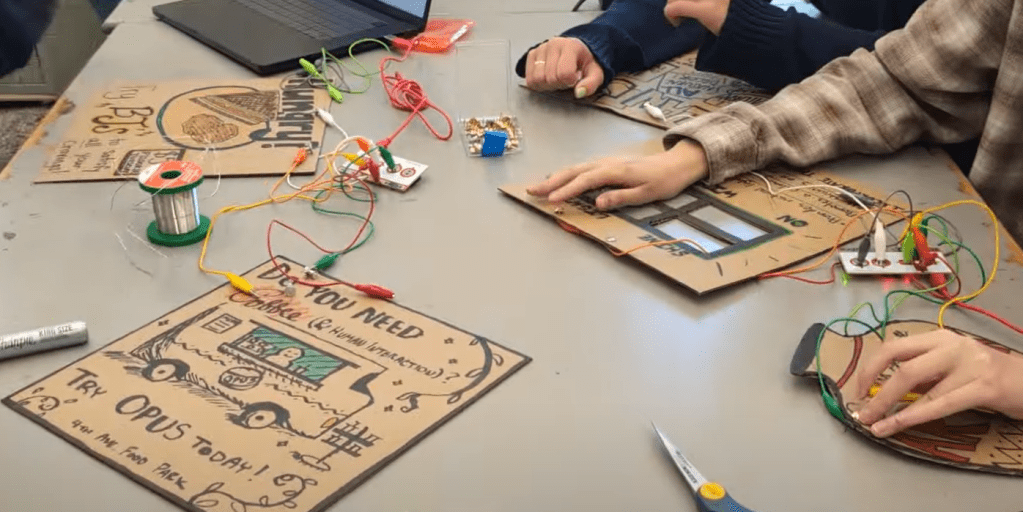

Students then partnered in groups to design product advertisements, using cardboards, color markers, Makey Makey, and whatever low-tech materials in the design studio. During this process, students reproduced the visual, audio, and logical perspectives of the design product, which are food, art & craft materials, as well as plant. We might ask “why call plant as a design product, which is supposedly embedded with designer’s labor and high technology?” The design student probably recognized the role of nature in human’s sustainability, through which plant played a key role in the designer’s ideology of health, innovation, and aesthetics. Thus, the student has expanded their understanding of design object practically, even before they were introduced with the concept expansive design.

When students played with Legos, low-tech, and then Makey Makey, they seemed to enjoy each other’s accompany. At first, they were shy in holding each other’s hands in creating a completed circuit for Makey Makey experiment. However, after recognizing the possibility of their bodies as conductive materials in producing impromptu sounds from visual materials, they immediately explored with different ways of connecting their bodies: some hand-held while others connected through copper wires. As students negotiated the role of their product advertisements with visual, sound, and dialogue, they were the center of the design studio. As a design instructor, I stepped back, observed, and documented their process of interactions and opinions.

As students visualized their individual design space while collectively patched the connections among them, it signifies the importance of collectivity in knowledge production and design process. More importantly, students found multiple ways to interpret their design spaces and design objects, which are often limited by the binary framework problem/solution. By picking certain design objects from the collectively built network, students recognized other’s shared positionality as an undergraduate design student body whose profession is built on studio arts. Most of the design objects were the physical make tools, allowing students to resolve certain problems that their shared positionality often experienced: morning classes with hungry stomachs, multiple deadlines of homework that students still figured out themselves, and many design programs that students were managing to use them efficiently.

If the design classes mainly centered students as the designers to solve other’s problems, students might have alienated their positionality as students, users of design products, as well as young people. They would have manifested the privileged positionality and knowledge of the industrial designer. If everyone is educated to be a leader, entrepreneur, and designer, then who are the teammate, worker, and user? Without being honest with self and other, the self-alienation to manifest other’s aesthetics and privilege would lead to pain, illness, and self-distortion. As a graduate student, teacher, designer, and user, I would not want such for myself, colleagues, or students. If the manifestation is painful eventually, then why would we keep manifesting such?

Acknowledgement: I thank my colleague Narayan Ghiotti for supporting this participatory design workshop, as well as Dr. Frederick van Amstel in design theoretical foundation, design material, and ongoing pedagogic supports.

References:

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum, 356, 357-358.

- Gonzatto, R. F., & Van Amstel, F. M. (2022). User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74(5), 758-781.

- Van Amstel, F. M. (2023). Decolonizing design research. In The Routledge companion to design research (pp. 64-74). Routledge.