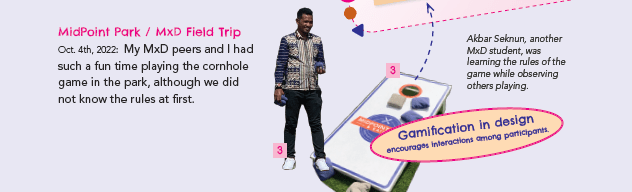

I started practicing ethnography observation since I entered the graduate design program MxD. I remembered the first time observing the nearby Midpoint Center Park, I simply enjoyed the space and had food. So engaged in the practice that I got closer to a diner in the wooden table and asked her what she thought about this Park. She looked up to me, opening her eyes wide while pushing her body backward. It seemed that I interrupted her lunchbreak. I was so embarrassed that I almost said sorry and ran away from her. But she said that it was okay. Not directed with a “go away,” I asked her several questions which seemed to bother her a bit more. I then decided to wrap up the impromptu list of questions, say thank you, and walk away.

I questioned myself without sharing that to my colleague: Am I the problem in asking her in my practice? Should I tell her that it’s a part of my research assignment? Am I wrong in asking instead of simply observing others in the space? But I do not know this space and people, so I thought it’s common sense to just ask?

Little did I know that at the time, I might have represented a friendly interrogator to a worker who might just wanted to enjoy her little time break. Moreover, I am a Southeast Asian international folk while she was a Black American female. The different positionalities as well as the cultures might have been challenging in holding the conversation forward.

Observation is a trained skill?

After our grad cohort came back from the ethnographic observations, we typed up our observations in the past 1.5 hours. While my colleagues commented several issues such as privatized park, inaccessible restroom, expensive food, and fake aesthetics, I was surprised at their comments, which were absent or not that troublesome to my perspectives. I mostly documented the beautiful flowers, the fun engagement across the cohort, which was the first time I hung out with, and the ‘local food’ that I also tasted for the first time. In a way, the problems in the park were naturalized in my perspectives.

But then I raised up the question in the studio: How could you observe the problem of design and link it closely to social issues? Is that a trained skill or is it an instinct as a designer? As in both personal and professional lives, I don’t normally do so.

I asked with curiosity as well as self-examination, wondering if I did something wrong. My colleagues were kind enough to explain their trajectories, where they were initially not having the designerly inquiry as they entered the program. Through time, the graduate training to made themselves more aware of the inequalities and social issues embedded in the surroundings.

As much as I appreciated their sharing, I felt that I was blind and had to depend on other folks’ worldviews to understand design better. Little did I know that each of us shared different positionality, including race, gender, social class, and handiness, which allowed us to see the world differently. At the time, I was just moving to Florida from Tennessee, where the diversity is opened up in its fullest scale, the road has the pedestrian sidewalk, and I saw the food trucks in the campus town for the first time to me. It was a gift of newness that I was not in the positionality to pinpoint the differences as problems, yet. My Viet friend’s words in her Catholic practice were more impactful to me than the readings on ethnography research “Who am I to judge?” So I built a habit of being grateful for what I received and read, while being polite and respectful for cultural differences among new friends and new space.

What I knew then changed the way I observed.

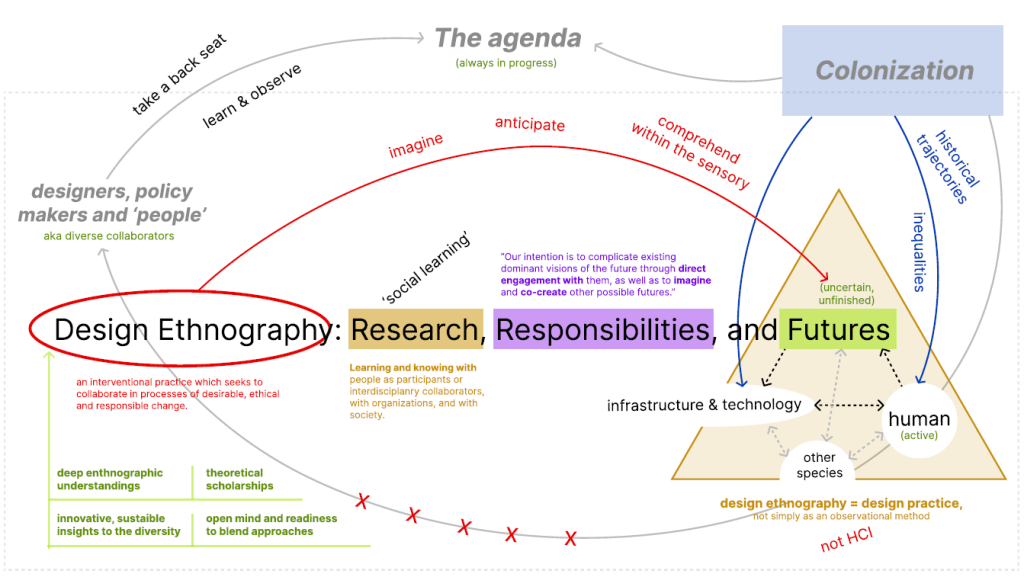

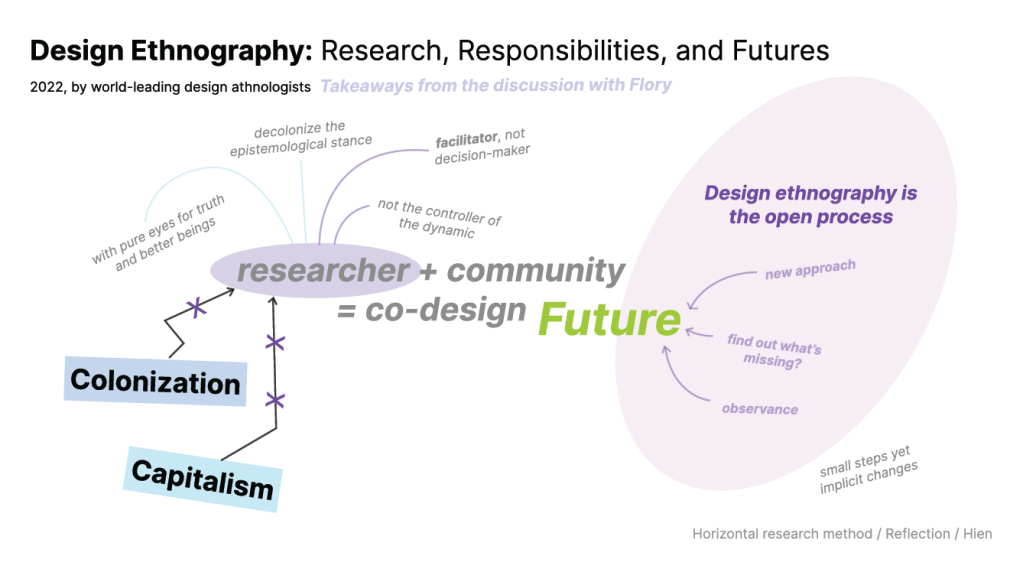

Years later, when I lived in the campus town in Florida long enough, I built up my examinations of the world around me, including the people and the system. I learned about the biases in histories and institutions through the critical theories on refugeetude, postcolonial studies, intersectionality, and how these theories are examined and applied in design research and practice.

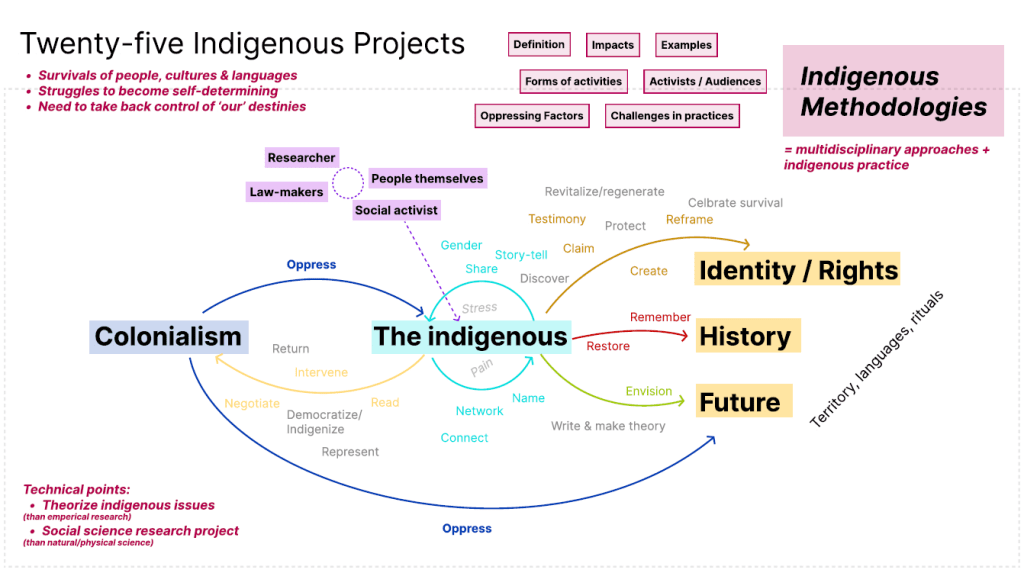

The world has been unveiled differently, even though it was the same place that I passed by to go to school almost every day. The pure joy with my colleagues was no longer that passionately there, as I was aware of the colonial history of the place that I stepped in. Even a beautiful coffee house in the university areas made me wonder if there was a link to the Indigenous people, working class, and immigrants. Through my professors’ support, I built the ability to read the history of the space, through paralleling theories, what I read, and observed. The overload of emotions was quite terrifying to bear, because it contrasts with the immersive, modern aesthetics surrounding me and the communal senses that I am supported with every day. It contrasted with the naive consciousness in my past self. It finally aligned with what I read but did not understand in “Twenty-five Indigenous Projects” (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012).

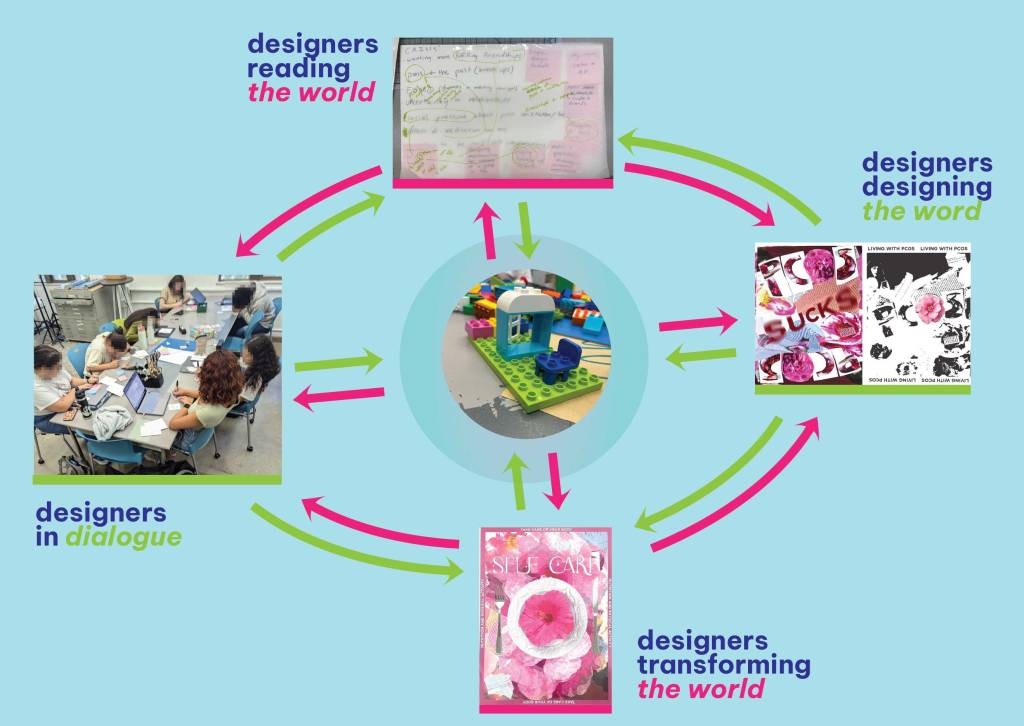

I started reading my world through the words from the literature in the elective courses, which I did not know about Freirean critical pedagogy to be critically conscious of. In those courses I did not have many chances to question because of the pressure in adjusting my amateur writing styles to the standard academic styles. Thus, I played catch-up with the theories in the readings while rereading them multiple times. I learned to accept the word choices and critical theories of the writers. It was a different world from my ethnography observations which are locally based and practiced. So, I deemed the theories in elective course as the foundation to compare my ethnographic observations with.

Not having much chances and skills to question in the elective courses, I moved to the design courses to display the questions, even they were quite far-fetched from what I observed. These questions hindered from the elective courses now incarnated in the visual forms. More pungent, more questionable, less celebratory.

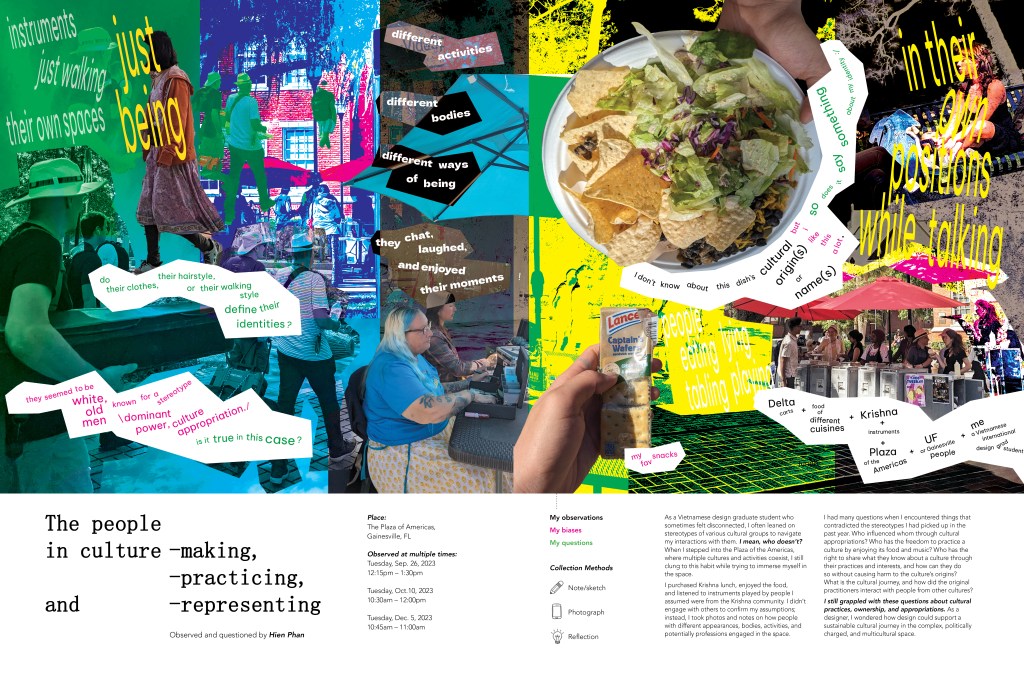

While white male is the symbolic representation of Western/European colonization, how do we understand the dominant presence of white male and white population in the Plaza of Americas where we observed? The one who shared about God in Christian, those in the religious student organizations, and the others in the Krishna Lunch who kindly served food and talked to me. Do I read them as they interacted with me in the ethnography observation, or do I lean on the critical theories that encoded the population to make sure that my worldview was not wrong? But I didn’t even know about their religions to comment about. I didn’t even know the expansiveness of colonization and coloniality. I was simply an outsider in these local ethnographic observations, having many questions but barely holding enough knowledge or similar positionality to comment. There is a gap between theories and practices that I did not know how to respond critically with. There is also a gap between who are observed and who I am as an observer. I remained a foreigner in many ways, to this place and to the people.

So, as parts of the design courses, I kept observing, silently questioning, and commenting as a semi-stranger. Some questions were not spoken out loud, as they were fermented while I was trying to see the connections between what I learn and what I see.

Among many questions I should not ask, this is the question I have answers for.

Since I worked on my thesis in institutional diversity using low-tech materials, there has been changes in what I observed, how I documented, and how I reflected on the observations. One of many things that I realized is that as a designer, I often shy away from critiques from others as well as others’ critiques, in observation and design presentations. While critiques were common in the design courses in higher education, critiques on the designer’s worldviews and ways of designing seemed hurtful and often defended with the designer’s personal aesthetic-bud. When ethnographic observations were documented and digitized, lots of labor were spent to make the aesthetics of the observations seem finished. Commenting on each other’s digitized ethnographic observations was like a professional procedure rather than a discussion of different worldviews, where bold questions could be raised to welcome critical answers. The conversation tones could be deemed professional, but at least we learned something new about things and people.

When high-tech played a crucial role in reporting ethnographic observations, it reduced a worldview to the deliverable product of specific standards. The specific scales of the deliverables already attempted to appropriate what to say and how it should be said. When being critiqued, I felt that both my design skills and critical thinking skills were confronted and should be fixed to serve the prospective readers. As a designer using high-tech in this process, I was commissioned to design rather than report, or to reproduce the aesthetics rather than question it. The high-tech space for visual design of the ethnographic observations was already the limit that

As much as I appreciated the ethnography practices, I learned to be critical of biases in ethnography that has been lured away by visual design, as well as the manifestation of critical theories in design practices that risked disrupting the genuine, authentic interactions. This made me move away from imposing theories to observations, as well as finessing aesthetics in ethnography observation for an accessible, universal, and inclusive piece of reading. Rather, I sought to engage critical questions through observations, being upfront of my worldview as a foreigner. This encouraged me not only to engage in ethnography observation but also autoethnography observation, where my worldview could be understood as an insider or a spy that tries to internalize and examine the surrounding cultures from the inside.

References:

- Freire, P. (1985). Reading the world and reading the word: An interview with Paulo Freire. Language arts, 62(1), 15-21.

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples.

- van Amstel (2024). Visual diaries, https://fredvanamstel.com/tools/visual-diaries