People of sports

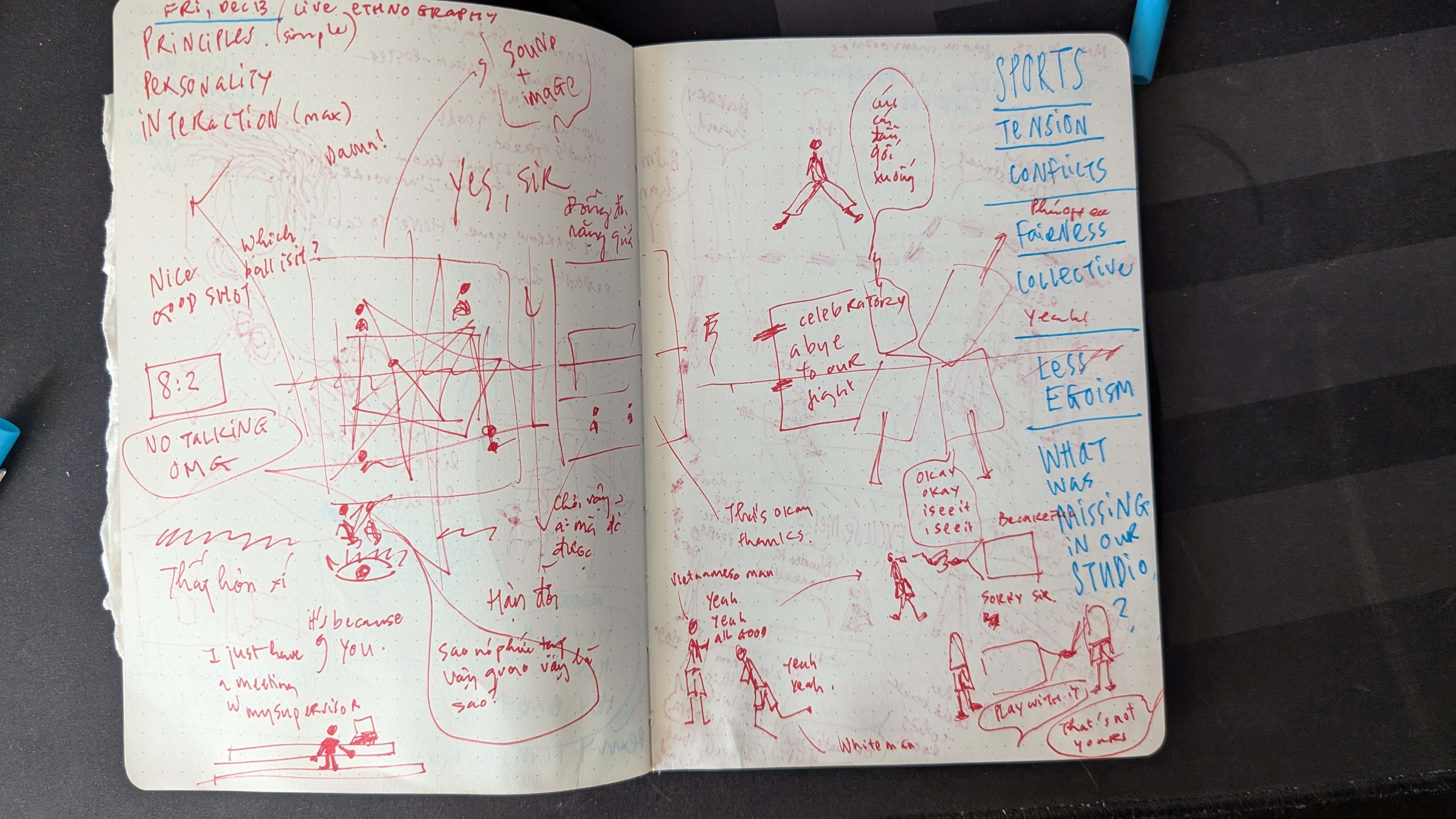

I knew anh Thuận along with other Việt friends since 2017. While the girls in our group bonded over little chats, the boys expressed themselves freely through playing tennis together. In the cold days, their energy filled in the court through the ways that they ran to catch the ball, cursed, slipped, fell, jumped, and laughed out loud. Meeting friends that know how to play tennis well and have enough time to play was like winning a lottery in a foreign land, even that only brought $5. Anh Thuận was willing to pay for the tennis membership at an indoors court although he usually calculated the expenses carefully. He could be a very silent, serious person but when it comes to sport, he was indeed an energetic kiddo. That contrast made possible by his interaction with sports was one of the reasons behind this comparative notes.

Chả mấy khi – he responded to me mentioning the pros of this membership, including the health benefits and friend gatherings from sports.

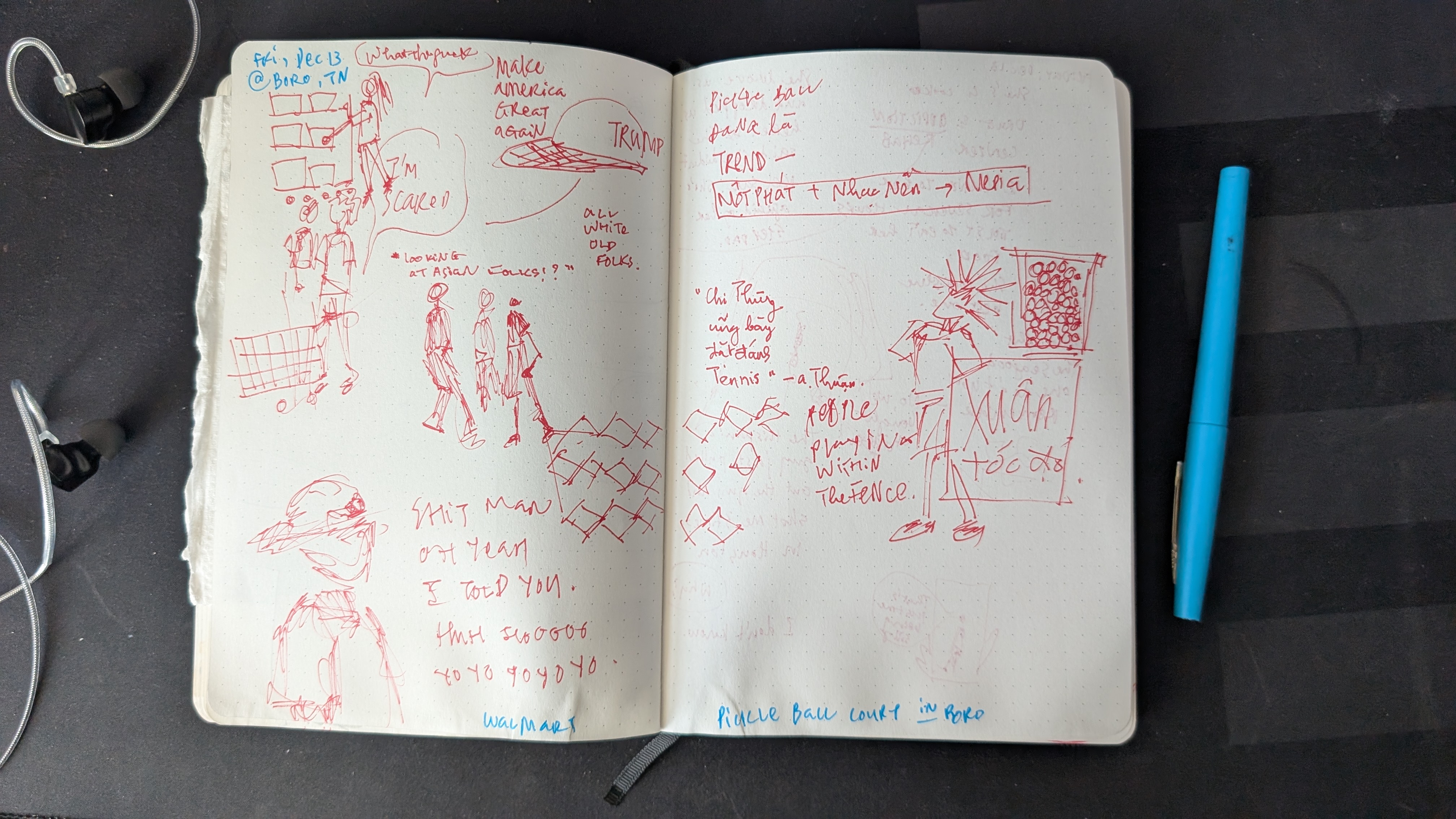

Anh Thuận played tennis since he was a little kid in Viet Nam. Although the sport materials are costly, his parents tried to support him knowing that he enjoyed and had talents in it. He was trained to play tennis competitively until there was an accident on his shoulder – from a tennis kid who was known for his talent in sports, he returned to classroom like other peers. The (blunt & playful) expressiveness was probably trained during his sport childhood, which was one of the common things that I’ve found in sport people. While respecting the sport rules, the sport people play creatively and strategically, and bounce their conversations from the sport space to their everyday space. This was how anh Thuận met the badminton club in his university in the States in 2022, from hearing the cursing in Vietnamese and tracing the sounds to a Viet friend in the vast court space. That way, they built community including Viet folks and many other folks who were willing to play badminton, pickleball, and then tennis. That was also how they decided to become roommates, shop groceries, and share many other activities together.

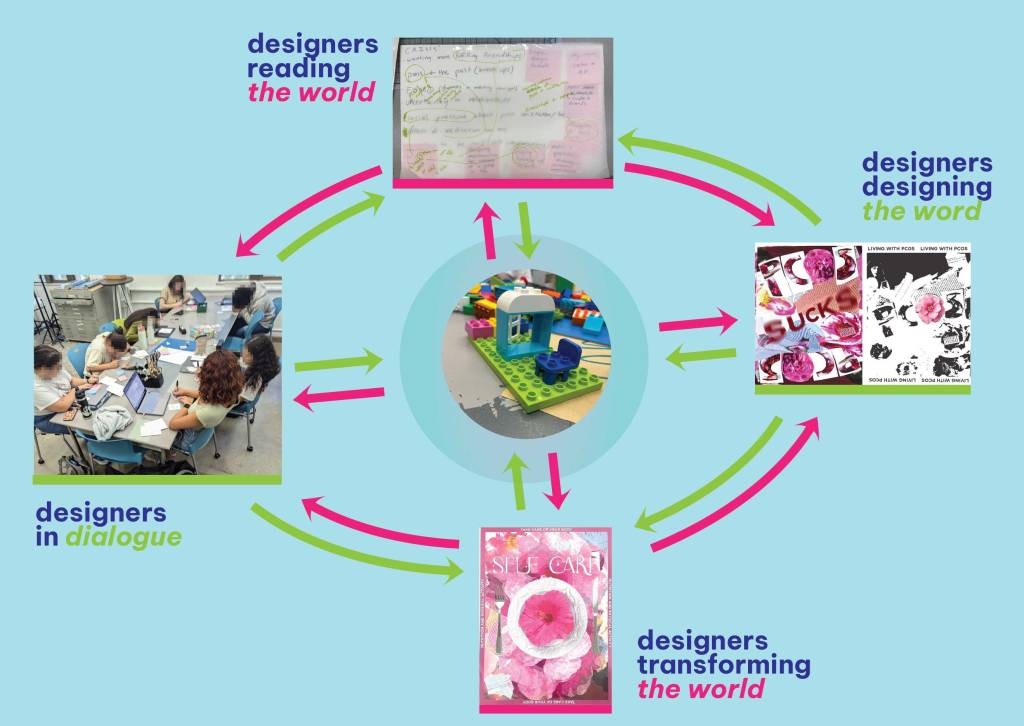

Seeing sport in relation with design

Sport is one of the toolkits to build community across space. In this case, university recreation center in Tennessee was the common space for playing sports, college student was a common positionality of the sport players, while badminton and English became shared tools for the players to interact and communicate in the space. When the recreation center was closed for the winter break, the badminton team went to a university outdoors space to play pickleball. Although pickleball has different rules from badminton, it was added to the group activities as a trending sport promoted on Instagram and TikTok. This global trend was adapted by the local space, including the campus town and the badminton club in Tennessee. Besides, the local people also brought their own paddles and balls to play pickleball. The design space was a part of the institutional spaces that allow many possibilities for interactions and commoning among players.

I’m observing the interactions in the sport space as a guest of the badminton club, a close connection with one of the good players who was also one of the roommates in a badminton household. I was also familiar to the university and this institutional space because I had spent more than 4 years studying and working here. In a way, I had the advantage of hybrid positions between an alum and current students, between a stranger and a good player, between the university and the apartment, and between the court and the space outside of the court, when tagging along anh Thuận in joining the badminton club in the winter break. From this standpoint, I did manifest the carrier of bird-eye view, who has the space and time to observe and document the design space, actions, and toolkits from a distant position, through camera and visual journal. Through anh Thuận’s relation with the club, I was able to observe the conflicts in the interactions in the club as symptoms of hierarchical power dynamics. The general understanding but lack of commitment to this club encouraged me to understand the incarnation of hierarchies from one institutional space to another, from the rec center court to the apartment, as well as from badminton court to pickleball’s.

Seeing conflict as a part of the diverse cultural body and neoliberal multicultural institution

The interactive space was spacious, allowing many kinds of communal activities: playing sports, resting, arguing over the game, and commenting on the game by other players. The good players would not mind playing with the beginners, but they had the capacity and strategies to make others exhausted by running across the court. During this exhaustion, the beginners could advance their sport fluency. Thus, beginners actually enjoy playing with the good players who could effectively level up the beginners’ levels. However, the good ones might not enjoy this kind of interaction that much, due to the lack of competitive flavors. So as the interactions among the beginners as they might not have enough skillsets in sports to share with each other during the play. Regardless, the club culture encouraged many interactions between all levels of players, because the players also networked through the sport. Advancing the badminton skills was not the only reason that they joined the club – it was also the opportunity to meet new people, get to know each other through the heat of sports, as well as celebrating the local holidays with the players in their own spaces such as apartments.

The badminton club, to me, is similar to the diverse student body our graduate design studio in the university. Similar to players of many levels with sport, we are graduate students from many cultures with a shared professional interest in design and design research. The diversity of bodies and discourse knowledge is the links between sport student group and the graduate program. However, the responses to hierarchical power dynamics in two groups are quite different, although all of the bodies are student bodies.

I got a chance to observe certain conflicts in a small group in badminton club. Due to the privacy of these conflicts, I could not explain the situations and impacts of these conflicts in details. When conflict is discussed, how this group approached the solutions is quite different – small groups were formed as a democratic space for complaints, blaming, curses, suggestions on dealing with the conflict, negotiations, compromises, consents, as well as dissents. They were unhesitantly straightforward, even some of the word choices was controversial with lack of disclaimers. There was no common pressure in keeping peace when dealing with conflicts, allowing each individual to approach the conflicts differently. That straightforwardness and non-hesitance with conflicts could come from sports or possibly the group made equally of male and female. Observing and participating in these conflicts, I understand that there are many ways in approaching the conflicts from a collective viewpoint, beyond the institutional responses to diversity.

Besides this club, I often see colleagues and professors in the universities here as mostly polite and nice towards a diversity of students. I was supported by this institutional narrative of inclusion, building the habits of responding to conflicts with rationality and politeness. Little did I know that this institutional response to diversity has normalized conflict suppressions, without understanding the root causes of conflicts in diverse cultures: When a diversity of bodies and cultures impart in one space, conflicts apparently and obviously take places due to cultural differences. However, conflict takes place in an institutional space of diverse student body which was considered as a threat to the performance of institutional excellence. I have observed how institutional narratives have eradicated individuals that were deemed at the root causes of such conflict. Thus, when conflict was eradicated by institutional narratives to ensure institutional inclusion, as Henry Giroux emphasized, it was an institutional attempt to terrorize non-institutional non-excellent non-representative body in the neoliberal multiculturalist education. As long as it serves the institutional excellence, diversity is welcomed and pacified to ensure safety, belonging, and inclusion for all, even that means the erasure of radical straightforward voices.

Thus, when conflicts take place in the institutional diverse student group, there was a common hatred towards a cause of such conflict. It was a common sense that troubles should not be made, voices should not be raised if it contrasts to the collective, consents should not given a chance to explain itself. Conflicts were avoided with all causes just because a shared space should be comfortable for all, even that means eradicating an authentic, genuine body is seeking for opportunities to make space for itself. Thus, autonomy and agency of a diverse student body is accepted and appreciated if it adds on the value of excellence and peace of the institution, which is normalized as the indispensable station of truth and knowledge.

If so, why does the institution itself need a diversity to co-opt to its institutional power? Why does the university provide many services to support the diverse student body and its existence depends on the satisfaction rates of student body, if itself is already a finished station of truth and knowledge?

Seeing institutional diversity beyond institutional space, where local conflicts and sufferings unveiled themselves.

Thanks to the neoliberal multicultural universities that the badminton club and the diverse student body could take place. However, this diverse body risks depending on the institutional narratives in avoiding or suppressing conflicts. If seeing politeness as the code of conducts in a space of diverse cultures, then the diverse body subconsciously admit the obedience towards banking education and institution as service design that aims to maximize customer satisfaction. Thus, joy, peace, and safety in diverse student body symbolizes the completeness institution.

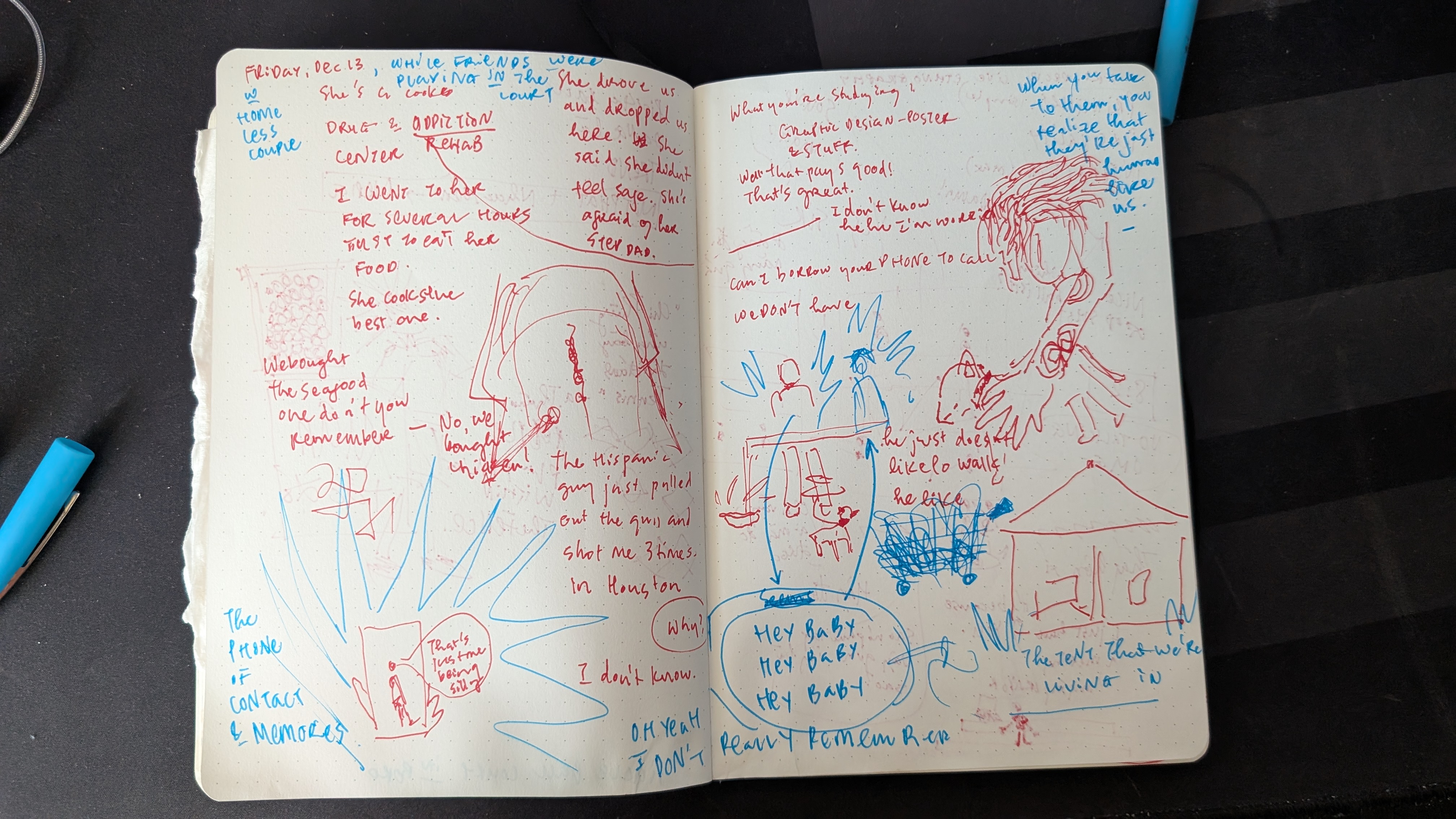

However, when I walked out of the institutional space, I saw the reality of conflicts in non-institutional bodies. I saw the traces of them, the people who were alienated and rejected by the rise of capitalism in institutional space – the homeless people. I didn’t pay much attention to them in the past few years as I have been indulged by the completeness of institution as a student, a staff, and a semi-teacher. However, during the process of researching about institutional diversity by design, I started paying close attention to actors and phenomena in the institutional spaces, including homeless folks. In hindsight, the desire to look at the institutional diversity through non-institutional lenses paved ways for me to see the homeless people as the void of institutions: the homeless couple around the university pickleball court in Tennessee, the old man with a bicycle in the Publix branch several blocks away from the a university quarter, and another man with a dark blue blanket the roundabout next to our graduate studio. This courage to meet and talk to them was crafted after my colleagues and I encountered a crying homeless woman in the Gainesville downtown and when we paused our conversations in the restaurant when another homeless person stepped closely to our table. This courage was created after professor Fred shared about the times that he encountered thieves and how he survived through dialogues with them in the past. This courage was fostered even more when I realized that after the pandemic, homelessness could take place anytime at any space to any marginalized people in the United States as a result of capitalism and individualist cultures.

So I happened to see and talk to the homeless couples while the badminton club was playing pickleballs in the public court. While my new group of friends met at the pickleball court, the couples were dropped from a car as the driver thought they might cause harms to her. When my friends were heating up their bodies with sport-playing, the couples pushed a shopping cart as if it was their house and stayed in a nearby rest station for sports. When we went home on that day, I did not know if the couples got sheltered in their blue tent that they just shared with me or not. They were just like any lovely couples that could love each other, but the status of lives was so different: we were the diverse college students pursuing a degree, they were the white homeless folks with lots of scars of sexism, racism, and classism on their bodies.

If you don’t trust these words, please start walking across the highly populated areas and if you’re patient enough, please start hearing what the homeless folks say to themselves and to you. Just like us, they must have been birthed from their parents, from the highly equipped spaces somewhere, and somehow have walked themselves or been pushed to the street. To know if there are links between us and them, dialogues and patient trust with the oppressed, as Paulo Freire suggests in the Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is needed for a collective transformation.

Due to the design of institutional space, these two bodies barely interact and have dialogues. We drove to the court which was closed to the recreational park while the homeless folks did not have cars and had the government reimburse for Ubers. The benches that we sat when observing the games could be the space that they slept that night. The restroom that we used could be a favor to these couples. The shopping cart that we used from a supermarket was like a mobile home to them. The food that we wasted in the bin could be a snack to homeless folks. The stories that I heard from these couples in Tennessee could tell something about the homeless crises in Florida, where highly ranked campus town was more brutal to non-institutional bodies, the homeless were pushed away due to hostile designs, and the state policies were more conservative, racist, and capitalist. What I am writing is observing at the design space of selves and seeing the possibilities of usage and inhabitation by others, as well as connecting the common links between institutional space from one conservative state to another in the United States. This way, I understand the institutional diversity that welcomes international Global South elite folks has been built as a part of the system that marginalizes the local social groups, creating racism and classism beyond the skin colors.

The more I research about design in institutional diversity, the more I understand about the expansiveness and invisible power of design. The interaction of sport created more responsiveness among players. However, when the interaction space is a part of the institutional services for diverse student body, it also plays another imaginary role of pushing away irrelevant users/consumers of the institutional services. Thus, if the diverse student body, especially the immigrant folks, only seek to redesign institutional services to benefit our own lives, does that also mean that we restrict our world and worldviews to the institutional space and services? Does that mean that we obey the standards of civilization based on how institution manage and pacify diversity through suppressing conflicts and, thus, blinding our worldviews?

Questions for you, me, and us when it comes to conflicts in institutional diversity

If my dear friends, colleagues, and future selves have enough patience to read until this line, then yes, I indeed want to talk to you as a troublemaker, a person who is curious of conflicts and contradictions, and a colleague who wants to invite you to altogether examine these conflicts as part of our everyday life. For whatever we believe in, ie. God or love, I wanted to ask you genuinely and desperately: How can we call ourselves (best)friends when our peace is actually a disaster to the silenced, absent friend? How can we celebrate a diversity of cultures when this diversity is already in the process of conflict suppression, pacification, and thus cultural appropriation? How can we forget a friend that spoke up the shared struggles of ours and got eradicated because their colonial worldviews are the opposite to the liberal, modern ones? How can we write a general quote to soothe someone with the language of “love” when we understand that there are unsolved, unveiled conflicts among us? How can we claim “solidarity” for ourselves when we are already distorted as elite liberal individualists? How can we hate capitalism when we easily share the aesthetics of our achievements on social media, as fast as a half of second? How can we teach others to think critically when we obey to banking education and manifest such banked pedagogy in professional practice and teaching? How can we design impactful, critical designs when we mindlessly consume a diversity of cultural products to co-opt to our individualist selves?

Of course, we can always run away from these questions, as I usually respond to my mom, anh Thuận, and my professor with procrastinations in professional works due to imposter syndromes. But we will design and educate for many more decades, having impacts on many others within the institution, including those who habitually follow the institution and who resists the institution with critical thoughts. Will we dare to skip the critical questions on how to deal with conflicts when we are and will be among the representative actors in institutional diversity?

Acknowledgements: This note is conducted after constant observations in a winter break in Tennessee, a trip to St. Augustine, and constant dialogues with my professor(s) on why designers l.o.v.e. to celebrate cultural diversity.