Sorry, I don’t know the Viet dish that you mentioned. You must be more Vietnamese than me.”

I often became passionate when talking about Vietnamese food in the United States, not because I loved it, but because I performed as a representative of this cuisine. That might have meant I was expected to know how to cook and taste this food properly and feel proud to introduce it to others. Little did I admit that I often felt pressured by this representative role.

When I became close to my friends from diverse cultures, they often asked with charm and respect, “What’s the local Viet restaurant that serves good Viet food here?” I often referred them to random restaurants that I knew were frequented by the local Viet community or employed them. It is common sense that Viet people own Viet food, but in the United States context, it is different. Most of the Vietnamese food here consists of recipes from the southern region of Vietnam: Phở is cooked in the southern style, bánh xèo, bánh mì, cơm sườn, chè ba màu, etc. I knew some Viet friends working in Vietnamese American restaurants whose families were from the southern region of Vietnam and had fled to the States many decades ago. I am part of the few whose families were originally from the northern region and migrated to the southern region for economic development.

I see Vietnamese cuisine in the States closely related to the Vietnamese American population. As a result of the geopolitics of Vietnam and the United States, this hyphenated label is used for the naturalized Vietnamese refugees and immigrants in the States. Food to Vietnamese refugees is political. It was an accessible means for this population to make a living in a foreign land, build minority communities, and sustain their belief in a nation in exile. Vietnamese refugees and their culture were mentioned in various ways in Vietnamese textbooks and media: dân Mỹ Ngụy, người Việt tị nạn, người Việt Kiều, hải ngoại, etc., from the dominant narratives of the current government. Food, among many aspects of culture, is embedded in their fleeing journeys after 1975 and remains a popular strategy for new Vietnamese Americans to sustain their lives in the United States service industry. While these dishes represented the history and culture of this population, they were also adjusted to the taste buds of the local communities, creating different ways of how southern Viet cuisine is served.

Although I am often seen as a representative of Vietnamese cuisine to my non-Viet friends, I humbly admit that I am simply a traveler, a guest, and an admirer of this Vietnamese American cuisine. I lived and became close friends with southern Viet friends during my undergrad years. Only then did I realize that I was not a typical Vietnamese who knew about the representative aesthetic Vietnamese culture. This aesthetic was far from my lived experiences. My mom grew up in the northern region, so she saw Hà Nội cuisine as a standard. She often stopped at Phở Hà Nội or Bánh bao Hà Nội when we grabbed food for school in Hồ Chí Minh City. My grandpa adapted the southern ingredients in cooking for our family but complained that it was too sweet for our northern taste buds. My uncles married women from the central and southern regions, thus adopting their taste buds, who mainly cooked in the household. My family’s lived experiences, thus, did not hold certain standards to food as we migrated to the southern region, adopting new cultures while sustaining certain northern taste buds here and there.

This is how cultural appropriation is normalized in urban contexts and family contexts, conditioned by local policies on migration and national development.

The first food container: non-institutional, non-industrial food in everyday contexts

This food container described the non-institutional diversity in culture which is not counted as the signature Viet cuisine. However, it showed the complexity and nuance of food in relation to class struggles and socio-cultural contexts.

The men in our family loved to have wine with đồ nhắm rượu (pairing food). Dồi trường and tiết canh were among the popular dishes that my uncles and grandpa cooked together. Food memories include moments like this when family members gathered around the food tray, had wine and food, and started arguing. These kinds of food and drink signaled heated cursing and even fighting and are often avoided by other family members, such as the women and children. Talking about aesthetics of national cuisine would simply neglect the social classes of the familial cooks and diners who were often burdened with many worries in daily life. We had many joyful and rough stories, which were different from the Viet representative dishes as part of diverse cultures in the United States’ neoliberal multiculturalism.

Food is indeed an embodiment of the socio-cultural contexts in which food designers are placed: how to buy ingredients with a certain amount of money, which seller to buy from so they would give our family a discount and extra ingredients, what are seasonal foods so they could still be delicious and cheap, how to measure the cooking time so all the dishes can be ready at the same time for a shared family meal, how to take care of the seniors and children in this meal when they are picky eaters, and many more how questions. These designers are my family members, the anonymous street food sellers I met, and even the live market sellers that suggested dishes to my mom. The food tastes depend on many factors in the design process: ingredients and the taste buds of the cooks, which are personal. However, these factors reflect local resources and the family members who live with the cooks.

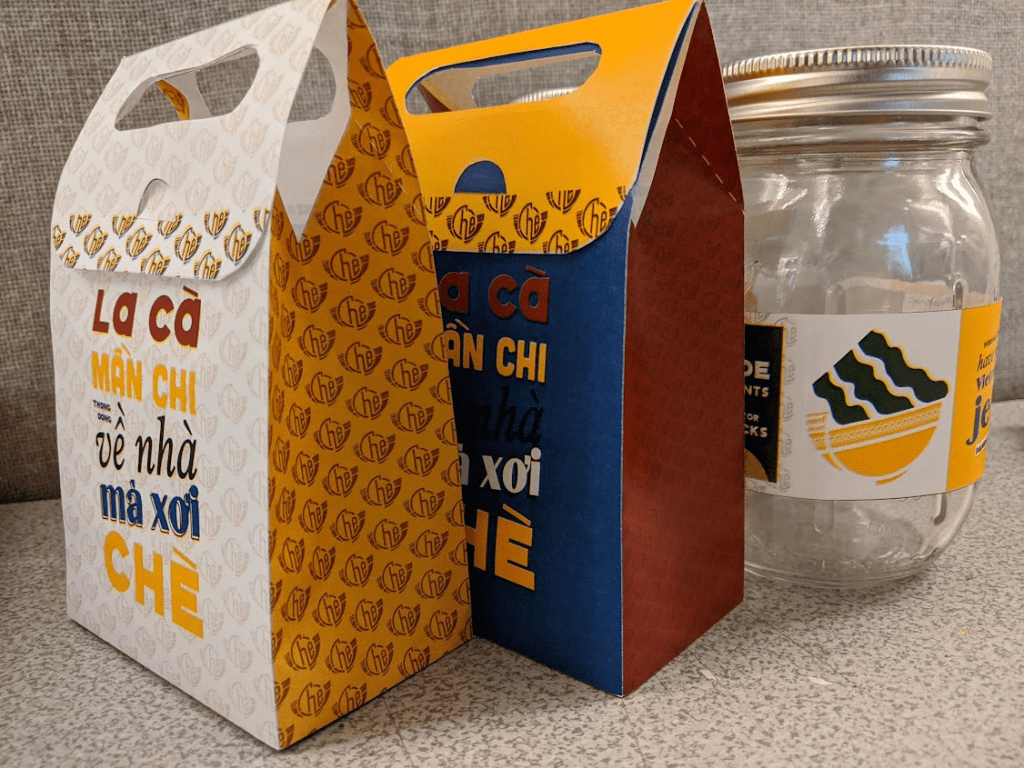

The second food container: “Our signature and also the best-seller Viet dishes that you have ever had in town.”

The other food container, however, shows how Vietnamese American cuisine is appropriated in the service design in the United States.

Food culture of minorities in the States is more than just the quality and authenticity of the food. It is also about friendly service, accessible space, mediocre adjustments to the local’s taste buds, and more. Serving minority food means measuring the taste buds, business possibilities, and generosity of both the majority and minority, the locals and the Viet, as well as the old and the young. Food service is designed by diversity, for diversity, which can be seen as a system of service by itself. A restaurant is a service by the owners, managers, cooks, servers, and cleaners as cultural designers that immediately responds to its diners as cultural consumers. Besides authentic, aesthetic representatives of culture, this service also values efficiency and benefits from this cultural business. Its success is measured by customers’ satisfaction and compliments although they are biased by nature.

Thus, the service design of minority culture is like an examination of one culture by many other cultures, which are altogether impacted by the dominant narratives of the local space, culture, and institution. Authenticity is undermined by the adaptation and strategic play of the designers of this minority culture and service. Authenticity is not needed in family meals but is strategized in business kitchens, service workers, and marketing teams. Authenticity of minority culture is impacted by how diverse cultural consumers are served, connected, and appreciated. In this case, cultural customers secured the dominant roles in minority cultural service through how they interact, examine, and perceive this culture through the served cuisine.

A few notes to you and me

The very first quote of this long note could be either from a Việt to another Việt, a Việt to a non-Việt, a non-Việt to a Việt, or a non-Việt to another non-Việt:

Sorry, I don’t know the Viet dish that you mentioned. You must be more Vietnamese than me.

Chu cha, sao mà mày biết nhiều món Việt thế. Chồi ôi, tao cảm giác mất gốc ghê gớm.

How much Việt or Vietnamese depends on one’s knowledge of the marketized, signature Việt cuisine and culture and, thus, on how such culture is embedded and embodied in that person. This note from me to you is to say that the marketized, signature Việt culture is simply a representation that risks misrepresentation as Homi Bhabha and Stuart Hall emphasized. This representation is the material-based mold of otherized aesthetics that discriminate aesthetics of everyday life that we live. It’s the aesthetics of cultural consumption and entertainment, but not necessarily the reality of existential practices of a person, a family, or even a nation that survive through colonization, industrialization, and globalization. This representative aesthetics is simply to alienate our own ways of living and appropriate us towards the standardized ways of living, by whom I would analyze at another time. Even how much the Việt was known of Phở, we still debated whether this is the Việt’s invention from the French colonization or the Chinese culture influence, which are both well-known empires in the past. Will you and me still love Phở as a Việt cuisine then? When you see the reality of non-Phở family meals frequented with class struggles as above, will you still love the Việt cuisine?

The love of Việt culture that you and I inherit and embody, in the context of the United States, is an industrialized reaction towards the product of representative media and Vietnamese American service. It is the language of convincing, marketing, performing, and entertaining. It is the language of perfect oriental aesthetics that is manifest through the viewpoint of the Western, the Disneyland franchise, and the colonial empires. Love, so as the representative aesthetics of culture, is bluntly an affection for exotic cultures – the lack of understanding the socio-cultural contexts of certain cultural production yet simply put as pleasant feelings to foreign culture. Love of culture is the abbreviation, masquerade forms of gigantic, in-depth relation to that culture, that is often abused by industrial entertainment languages.

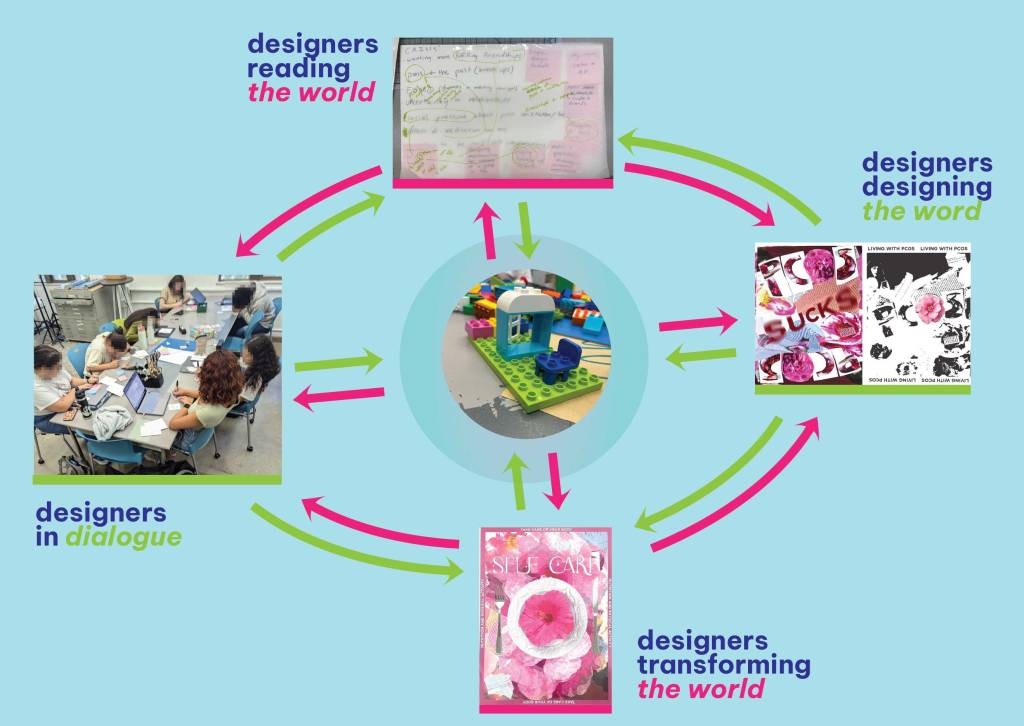

Design process

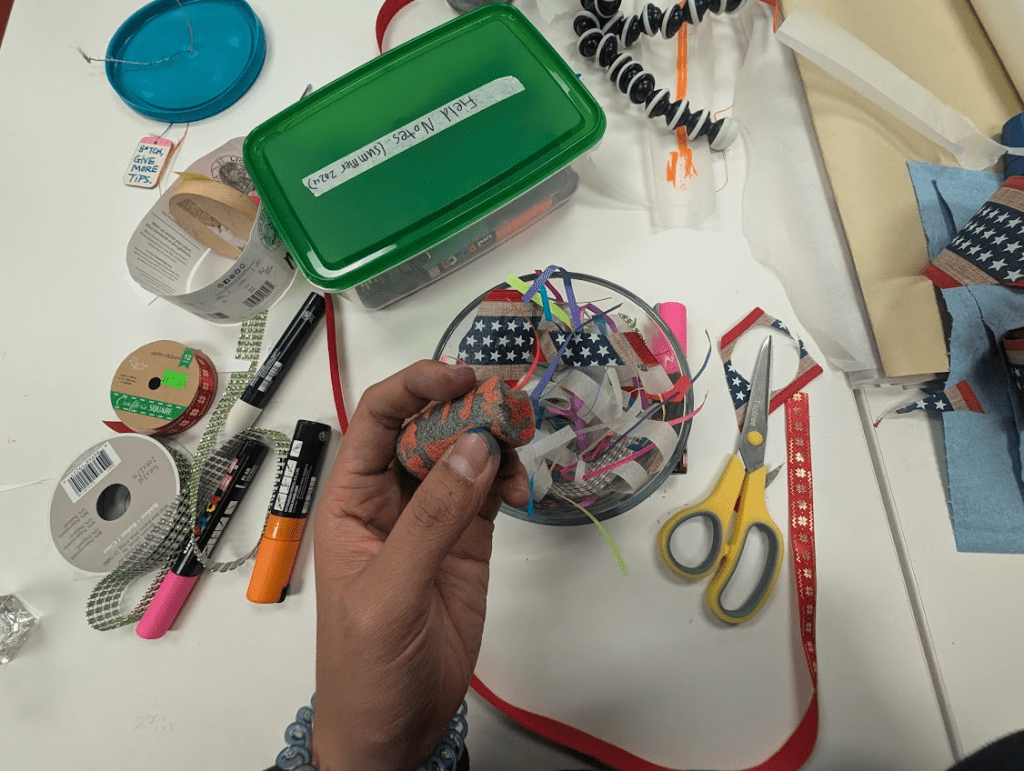

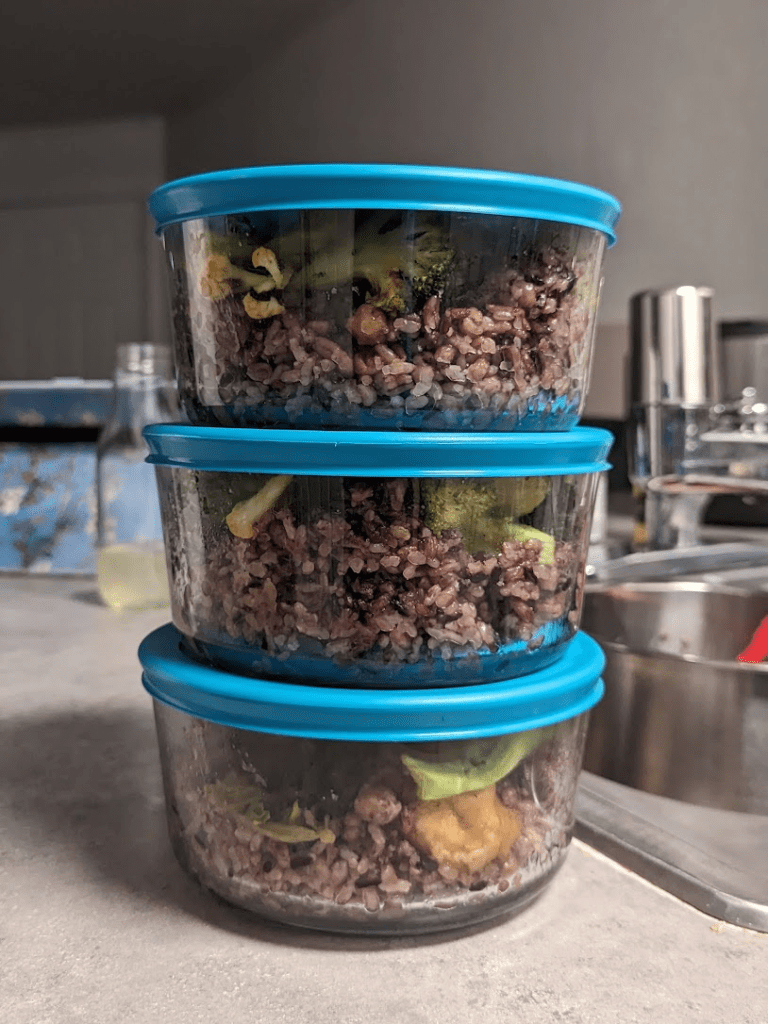

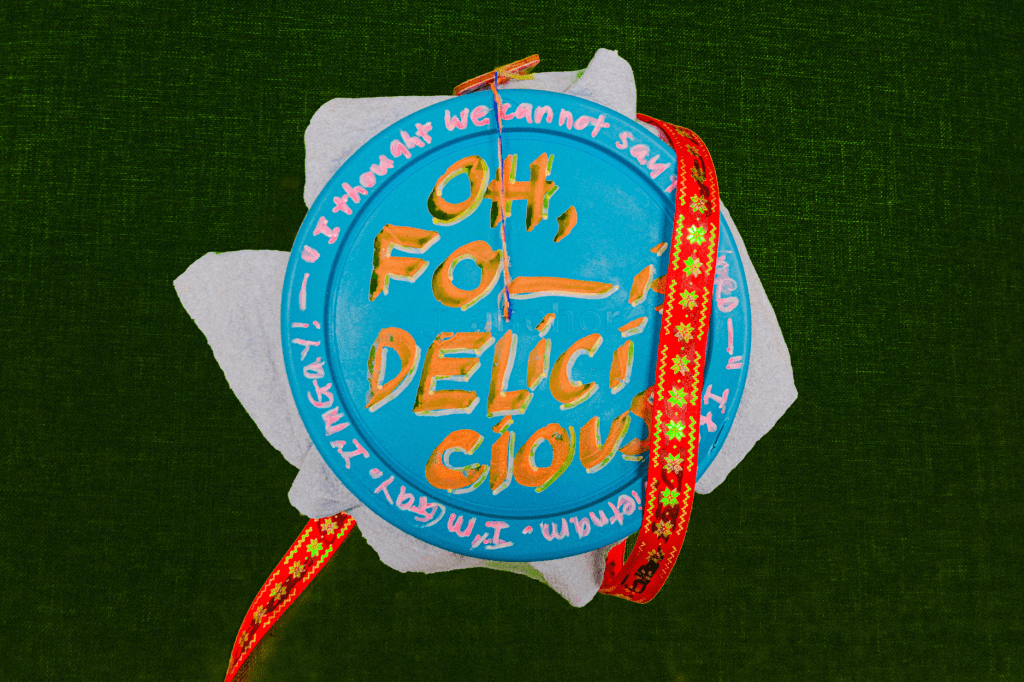

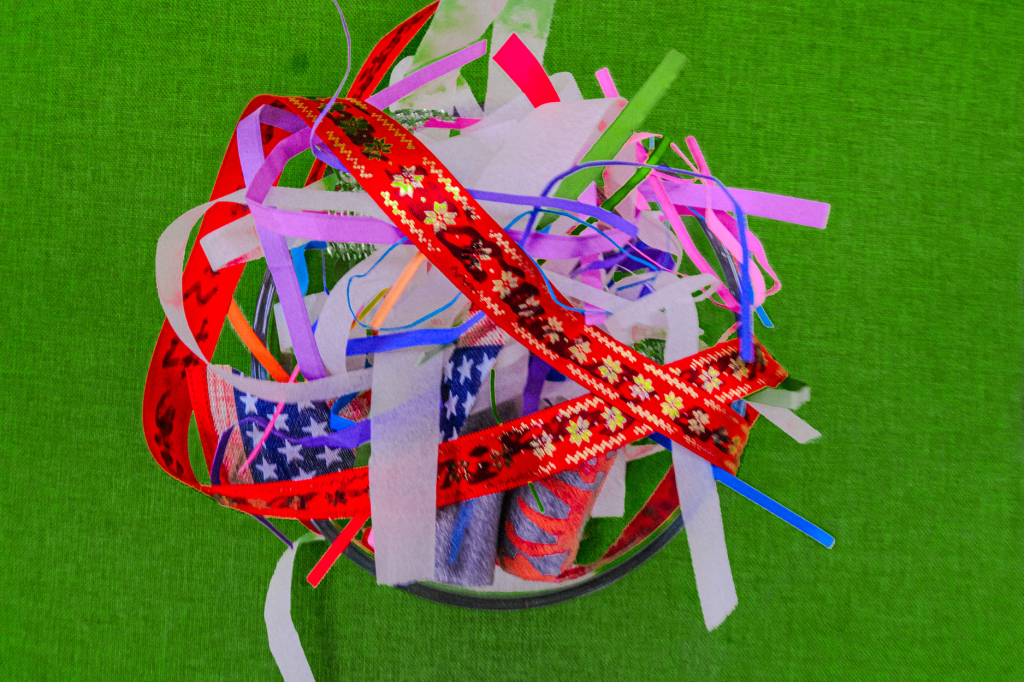

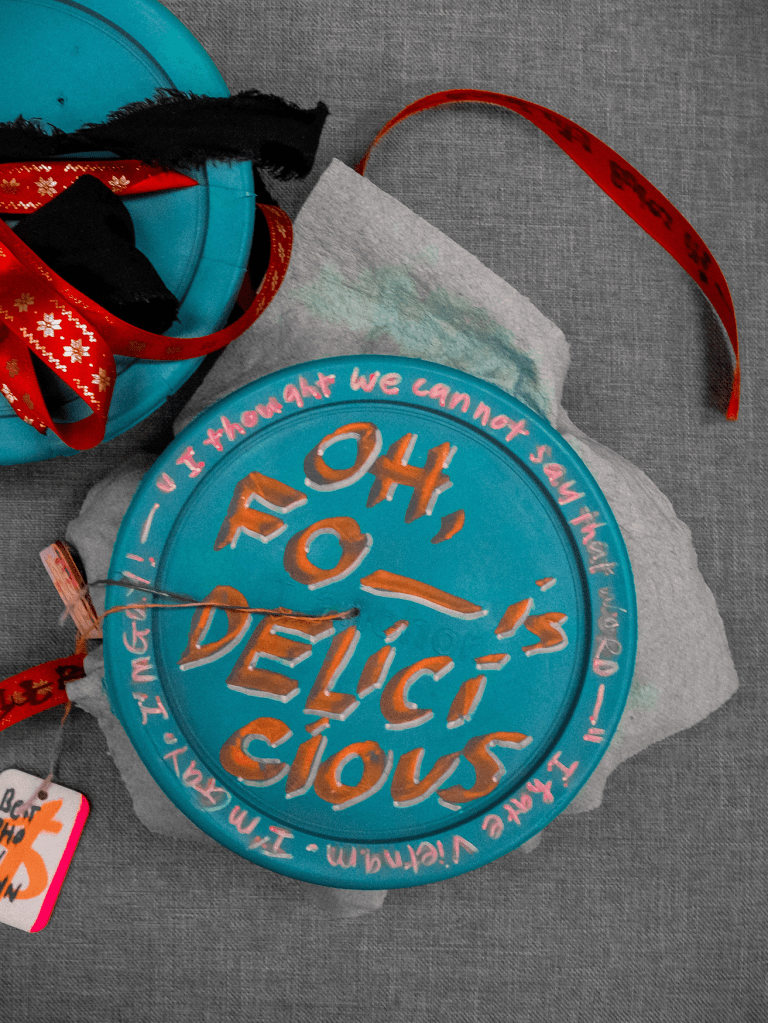

This design was made from “local” materials. I bought the Anchor containers from local Ross, sourced DIY materials from Repurpose Projects, and markers from Amazon. These materials were global to me as a Global South designer, regardless.

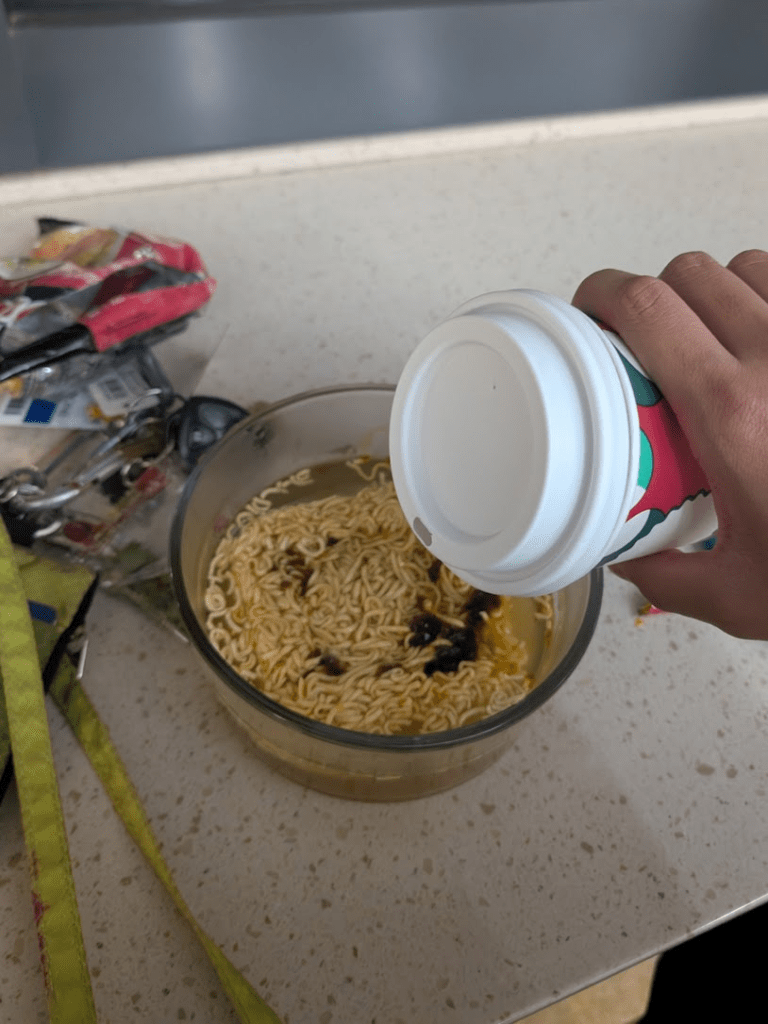

It was a sparkling thought of food in relation to culture and service design, so the design process was an experiment. The industrial, global materials were messy, broken, chaotic in the design process as a resistance to the globalized, industrialized representation of culture that, as a token of diversity, I often played without much chance to critically think through. This design process is a period of reflection. After a while simmering and fermenting this design, I revisited the taken photos and exoticized them with Adobe Lightroom.

When I was writing this blog post, I analyzed the materials and symbols in design by revisiting the relevant memories which could have been deeply embedded in my brain or my camera roll since 2017. The memories were either in the context of home in Vietnam or institutional spaces such as grad studio, library, and college apartment. This process expanded the understanding of the designer as a design body or technology, while patching and examining the designer’s perceptions is a design technique.