In comparison to developed countries, inclusive design and accessibility are absent in developing countries.

In the winter of 2021 in Murfreesboro, I applied for grad school in design. That same season, I received a call from my mom informing me that our youngest uncle had passed away. He was around 40 years old at the time, had had Down syndrome since he was very little, and did not wake up one morning when my grandpa shook his shoulder on his bed. I’ve heard from my mom that he developed the syndrome after a severe fever. My grandparents were struggling to raise seven children at the time, which might have limited their access to health, education, and economic resources. We did not have much time to revisit these stories because the adults in my family were always busy making a living. Thus, as his niece, I had very little information about him. When he passed away, my grandpa cried a lot – it was probably one of the very few times that we saw the oldest man in our family become emotional.

I wrote about my uncle in my grad school application, with the thought that he could have been treated better with his disability. Because of the lack of access to specialized health information for disabilities, I naively assumed, our family was not able to provide him additional care. We knew him as the uncle who carefully took care of nieces and nephews, but he appeared as a silenced member in family settings. He loved humming, walking on the small road in front of my grandpa’s house in Đà Nẵng, and holding children in his arms. One time, he walked too far from my grandparents’ home, almost to the outskirts of the neighborhood. My grandparents found him and would never let him walk alone again. As they grew older and could no longer keep up with him, he was often kept within the house. In comparison to children with Down syndrome in the United States, his living space was much narrower, his interactions with others were fewer, and his lived experiences were more limited. Perhaps that is why my grandpa cried that day.

In hindsight, I compared the accessibility for disabled people in Vietnam, a developing country, with that in the United States, a developed country. The contrast was stark. The lack of equipped spaces and services in Vietnam was far less than in the States, which influenced our family’s lack of specialized care for my uncle. However, little did I connect to the fact that my uncle was born in the northern areas of Vietnam shortly after the national liberation in 1975. When the country was still recovering from Western colonization and wars, its people focused on agriculture and industrialization. In families, both children and parents worked to make a living. While parents moved away from their quê quán – birthplaces or hometowns – to earn money, the older children worked for wealthier families to afford living spaces, daily meals, and schooling. At home, grandparents took care of the younger children. They probably barely had access to sufficient materials for basic living, let alone the special care my uncle needed.

His life depended on other family members, just as the disabled depend on the able. In comparison to the abundant accessibility signs in the United States, there were few to none in Vietnam. While my uncle depended on my grandpa for food and feeding, there were designated routes in the buildings of my universities in the States. While my grandpa followed my uncle on familiar roads in our neighborhood, there were wheelchairs designated for the tired, disabled people in the States. While my family chatted, joked, and ignored my uncle, there were designated spaces and materials for education and entertainment for people with Down syndrome in the developed world. In contrast to unguided human interactions with a disabled citizen in a developing world, there would be inclusive design in response to diverse disabilities in the developed world. Design for the disabled is a means to achieve the standards of the able, without necessarily questioning those standards. Design for diversity is a means to achieve inclusivity for diverse people, without necessarily questioning the social context and intention of such inclusivity. Standardized design for accessibility highlights efficiency in care for those who have not yet accessed the standard, thus industrializing care under the guise of “accessibility.”

As a family member of a disabled person and a designer, I see the value of inclusive design for accessibility. If these designs had been present in our family, institution, and community in Vietnam, my uncle might have lived a different life. However, as his niece who lived with him and observed other family members’ care for him, I want to critically assess inclusive design through the cultural lens in which I was born and raised. Only after moving to the United States did I learn about the many possibilities for people with disabilities and how they were included in shared spaces with others, showcasing the diversity of space and institutions. Design played a crucial role in this process. Regardless, what I am analyzing is to contextualize inclusive design within the socio-cultural settings where design is often perceived as synonymous with industrialization and modernity. Inclusive design was absent in Vietnam not because the country wanted to exclude the disabled, but because we had not developed the material conditions to include them. Importing inclusive design from Western developed countries after gaining independence from them seemed ironic—just like returning to foreign molds.

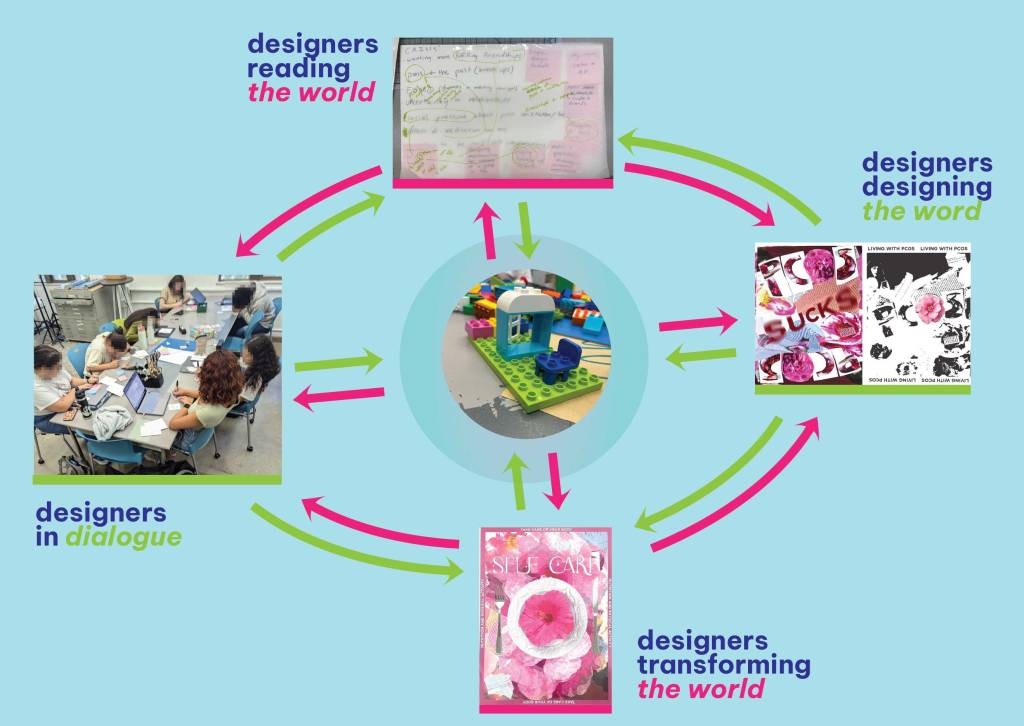

As a Vietnamese designer studying and practicing this profession in the States, I am critical of inclusive design as a way to critically assess my role as a designer. I am part of the collective body that manifests modernity in design, which was sprouted by Western epistemologies. This manifestation could turn into enforcement, alienation, and otherization in designers’ relations to non-Western bodies and spaces.

Modernity in inclusive design displaces traditional spaces and bodies.

Disability is labeled for any unconventional form of human being to be treated with more care, including the elderly. In airplane services, elderly Vietnamese people who don’t speak English are advised by flight consultants to use wheelchairs, supported by service staff to navigate all necessary steps in the airport and airplane to English-speaking countries. This service works efficiently because the service user can travel through the service space without knowing the space and the language of the space. Thus, this tip was systematized in the flight service suggested to my family. In December 2022, we booked a flight from Hồ Chí Minh City to our quê quán Thanh Hóa through my mom’s friend. My grandparents were suggested to use wheelchairs for the convenience of family travel—the young could wheel the old without much hassle navigating through the airport. When I discussed this service suggestion with my mom, she scolded me:

Đang lành lặn tự dưng bị đẩy đi như què quặt. Ông bà chửi cho đấy. Dẹp đi.

Their bodies are fully fine, and now they are asked to be wheeled like malfunctioned ones. They would be mad at you for hearing so. Stop the fuss.

In a way, accessibility through design is redundant to human bodies that have design abilities themselves. Using inclusive, accessible design means denying the abilities of the design body. The efficiency of these designs is deemed a threat to agency and even the future possibilities of the design bodies. When inclusive design is used for efficiency (or, to be more critical, laziness and carelessness), it risks denying and destroying traditional cultures. If we see inclusive design as the embodiment of Western epistemology, this design persists coloniality in design while its users can be seen as the colonized design bodies.

So we ended up not using wheelchairs for flight preparations. Throughout the trip, we supported our grandparents in stepping through the escalators in the airport, the stairs in the airplane, as well as downstairs. Carrying their hands on our shoulders, reminding them of the steps, as well as convincing them to tag along with us instead of walking too far on their own.

We were design bodies ourselves, replacing the service staff and the wheelchairs, understanding the autonomy of the elderly when they were with their (grand)children. Inclusivity and accessibility in service design, in this case, became a silent mold, in which the autonomy of users is undermined as stubborn rebellion which needs to be eradicated for peaceful management. Efficiency in this design means that user’s labor and time could be eased out by user’s money for available design service and technology.

When efficiency is highlighted, tradition is easily replaced by modern design as how human bodies are replaced by design technologies. When modern technologies fill the traditional spaces that were heavily based on natural resources and human labor, that is how our developing world mimicked the developed world even after we fenced our world. Below are some examples of how traditional space is recently filled and displaced with modern designs through urban planning in our quê quán Thanh Hóa.

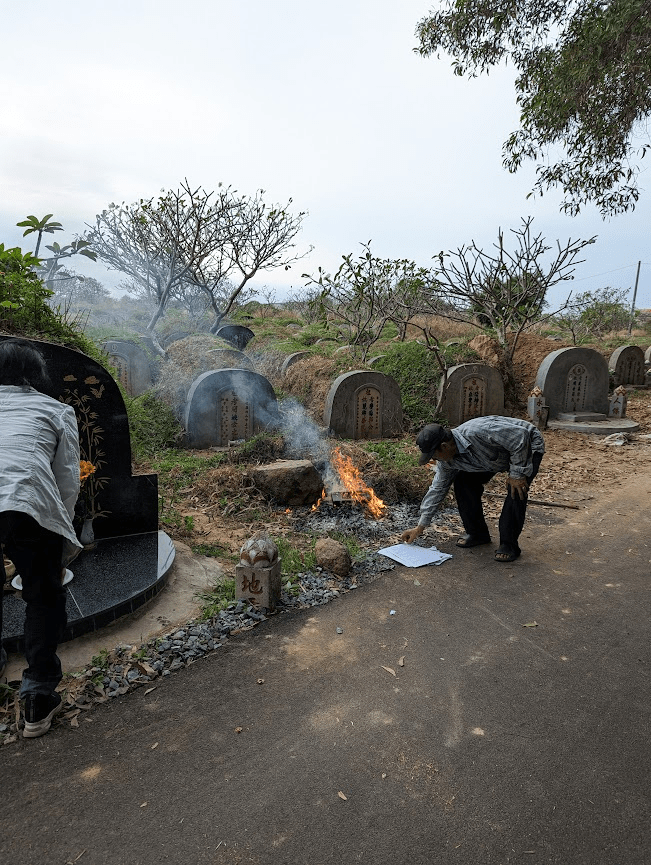

Our quê quán was modernized—my grandparents’ acquaintances no longer lived in the old places that they were at. They moved, as did my grandparents’ workplaces and their relatives’ graves. We visited Thanh Hóa in reminiscence, in the hope to satisfy our seniors’ homesickness that had been suppressed when they followed their children southward to Vietnam. The flights and taxi drives made their feet tremble, their ears hurt, and their backs sore, but they bore the modern vehicles as the designed access to their past, their birthplace, and their lived memories.

Đấy, quê choa đấy. Nơi chôn nhau cắt rốn của mi đấy.

See, our motherland. The place where your umbilical cord was cut and buried.

After they stepped their feet on the dirt road, my grandparents seemed to revive. The mixed fume of cold air, live market, and house plants hugged us well in this space, which were deemed old-fashioned or casual decorations of modern spaces in Hồ Chí Minh city. My grandparents carried several kilograms of heavy coats, their cheeks crackling red, while their feet moved non-stop to the people that they had met before their children moved them southward to the economic development areas. The elderly held each other’s hands dearly, sniffed the faces faded by time, asked about who had lived and died, wished good health among themselves, and asked their children to take as many photos as possible, as if it would be the last time this gathering would be possible. Modern design was needed to travel from the modern space to the traditional space which was gradually replaced by modernity. Traditional bodies like my grandparents and my mom were challenged by modernity while their children were equipped by these modern designs in their lives. The intergenerational dialogues and care, thus, is a resistant band between modernity and traditionality, despite the availability of modern, efficient, inclusive, whatever-fancy-word design.

If limiting inclusive design to non-body efficient, accessible technologies, we indeed would neglect human interactions to these designs which adapt themselves to be humane design bodies.”

Acknowledgements: This is sprouted from scattered conversations with my mom, my grandpa, and Dr. van Amstel.