Usage habits are built around and within service design.

In January 2022, my partner and I visited New York city for the first time. It was my first time using the legendary subway system in the urban area. While my partner was focusing on the navigation through Google Maps, I was following his footsteps like a little tail and taking a bunch of photos on my way. I did not want to lose a sight of New York. In June 2023, my colleagues and I visited New York for our conference trip. I followed their steps who have been to New York for more than 3 times but gradually wanted to explore the subway system so I could go to more places. In October 2023, I booked an airbnb far away from the Times Square, carried a baggage-weight bag from the airbnb to the conference. Like homeless folks or a Tây ba-lô đi phượt, I carried by temporal world on my back for several hours passing through the crowd and letting my feet lead the way until they were sore. I stopped by random shops on the way, Paris Baguette, Seven Eleven, and souvenirs stores. The night was not rushing, no eyesights to be pressured by, no money to spend, no friend to be invited, the Pro-Palestine protests were started somewhere else in the same city but not in the luxurious side that I was at. The night was ended when I booked an Uber to the airport for a stayover on the white cemented floor.

I had a habit of sleeping through the airport when visiting family and friends in Tennessee. It’s a forced habit that I learned to live with less complaints. It was a 2-hour drive to the popular airport in Florida, rested there overnight with at least 20 more families in the check-in station, and got ready for the very first flight of the day in 5am or 6am sometimes. The early flights are often the cheapest so I could save some for long-term car parking near the airport. The travel time and vehicle, indeed, asked for many personal adjustments: light packing, airport stayover, treating strangers as friends with the faith of mutual respects and supports, and many other things. I forgot that I am an Asian female foreigner in this space, as the familiarity with hardness has trained me to see others as helpers instead of threateners. I did not want to bother Floridan friends that I just knew for a drive, and because I was among the few foreigners who have a car. The privilege in unprivilegeness reasoned for my habit of finding ways to work with what I have. With the limited time that I have, complaints could bring many helpers on my side, but surely cuts down the time that I have. To make my complaints reasonable for help, I would be pressured to legitimize my stories for others’ empathy and despise those who were too busy to give me their empathy. My complaints could raise higher possibilities for others’ helps but indeed lower the possibilities of wayfinding my own solutions. Because of this, I did find ways to work around the vehicle options that I had.

Recognizing alienation in the mask of efficiency in service design

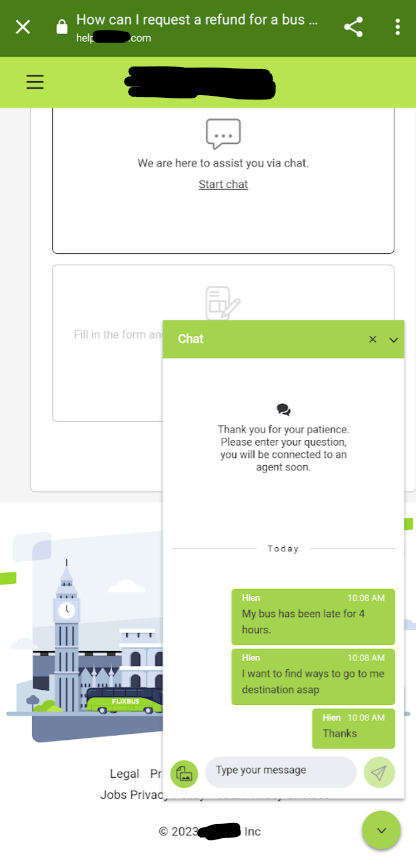

In May 2023, when I used the [Brand X] bus service to travel from Nashville to Gainesville, it was literally a nightmare. Along with other passengers, I was stuck in Atlanta from 5am to 9am at least. We asked each other from the seats in the waiting station, wondering why we were all dropped here for so long. From the corner of the station, we were starving, hearing the smell of the sloppy fast food chain and the slippery bathroom nearby. I could not sleep, running out to ask the station staff more than once. I’m sorry, we could not do much, the staff shared. The bus driver was nowhere to be found, I’ve heard. But there would be other buses driving pass Gainesville, I insisted. Yes, but the buses were already fully booked and we could not add you on to those buses – sorry, ma’am.

Finding a new seat, I opened my phone and look up some contacts. Should I demand a meeting with a manager? Should I leave a bad review like others in its Google Map? The service staff were puzzled and indifferent. As if complaints could make a bus driver out of them or I could be located to home rightaway somehow. The staff were hired this earky to respond to complaints with mechanized politeness, calmness, guidance, and apology. Any complaint dedicated to the system could exhaust the staff and not the system. Even the “system” responded to me with the most professional apology which I did not need at the time. Service staff were like the sandbag for service users to punch desperately, release the stress, and revisit the reality with less space and time to complain. The sandbag in service made up for the absence of crucial actors: a missing bus driver, the system who allowed cheap, early service; and other unknown actors. As the responsive service exist but did not resolve the complaints, both service designers and users learned to bear the holes of both service design and usage. These holes, sandbags, or mechanized responses undermined agency and humanity of the service staff and customers in this process, even during the burning crises.

Thinking about the list of homework that I need to finish for the next day, I could not bear the obscure responses of the service staff and tiredness of the crowds. Pressing the madness deep inside my stomach, I left my seat. I sneaked out through the door of the waiting areas and stepping out to see the buses waiting on the main street. Out and in for a while, I saw the big men arguing with the staff outside while inside, the old folks were tired from the first bus drop since early morning. The men seemed to find the negotiations with the officials and stepping up to the bus, I overheard. I walked to the officials, asked to tag along to the bus because I was already tired waiting. I was measuring the possibilities that were denied by the service as “fully booked” and “impossibile”. Without argument, I was allowed to step in the bus, following the big men who were already settled with their seats. Through the bus windows, old folks were still sleeping. Other folks ran out through the same door, taking the last spots in the bus.

As a designer who is tasked with efficent easy-to-follow guidances, as well as ensuring the quality of services, I am the troubling user who sees the limits of automatized design. The transportation services let me know that midnight-early morning departure is the cheapest, but possibly the most fussing one in comparison to other time slots. The cheap price is made of irregular functioning time of both service users and providers, making crises and apology conventional of services. When both in-person and remote service support became helpless, there was nothing much but leaning on autonomy of self – of users. In a hindsight, being a 20s Asian female service user also studying and practicing service design in the United States potentially allowed others to perceive, support, and approve me differently. This made me think of the old passengers who were too tired to stay in line for service questions or follow our steps in the last bus. Even as the users of the same service, we shared different realities because of our different positionalities.

In this scenario, customer service is designed to silence complaints with apology, which aligns with the professionalism in a modern, civil design system. The bus service brand is designed with an iconic running horse, just like strong animals as the mascots for cars and engines. Service was marketed with more-than-human quality [fast, on time, clean, illustrative, and accessible] and when it makes mistakes like any human-beings, it asks for empathy because of its dependence on human. Service design raises the expectations of labors and services for its machinary revolution, but when it fails, it leans on the reality of imperfect human-being. Service is designed to suppress the madness in users, demanding the users to be humanely responsive because its service workers already apologizes, although they might not care enough. How could they care when the faults are not done by them, but possibly their exhausted colleagues and the service designed based on social classifications? The service staff would neither care much on users, service, nor their colleagues because they were not trained or paid enough to resolve the complexity in human interactions. Segregations in service role (designer/user) and work positions (consult/drive/book/security/etc) are designed and sustained to maximise efficiency in service function and minimize human conflicts, which persists alienation in service design.

The alter/native of alienation in service design: is it primitive, less-than-human?

United States is where I learned to be a service designer and provider, besides its user. Service here is categorized by many discourses, with specific policy and license to operate. Long paperwork with meticulously described categories are normal process here, for both service providers and users. In my first time signing lease contract, I was reminded of my friends to read through the twenty-page contracts carefully to remember not to make a mistake and get penalty. Even a work-out class in the school recreation center demands a penalty if I were late to it. Outside of school, when a service user misses a class, they have to pay certain amount for it. In a way, the service business makes a living not only based on users’ usage but also failures in using those services properly. Many categories exist in service are there for both service staff and users to follow and not fall out of such categories. Otherwise, money, effort, or time are among the penalties of crossing the boundaries of such categories.

In Viet Nam, these categories are increasingly enforced by legislation and policy. In Hồ Chí Minh city, helmet was compulsory since I was in primary school, cars were recently populated, and many roads as well as subway stations are being built. We looked up to Tokyo and New York like big icons of urban planning and transportations, but the people indeed do not like regulations and categories that those systems bring along. Street food sprouted on the side of the streets for construction workers and parents who drove students to school. I often bought a quick breakfast from a Sticky Rice auntie when my mom stopped briefly at the red light in the large quarter – less than 60 seconds for a service of all steps and I would had a mouthful of well-seasoned rice when it turned green light. Minimal policy in service woke the children with maximal street view, appreciated how quick the auntie and her husband in serving us, and reminded us of the mixed smell of nearby food shops and Contruction sites. Nothing were bound, indeed.

The street food carts were attempted to be removed from the pedestrian sidewalks for the idea of beautiful, clean, and green streets, but failed. More buildings and subways are built across the river in Hồ Chí Minh city, but the modern regulations could not bind our culture, society, and politics. When we bought food from the street, we bore the risk of not seeing the food cart one day because the sellers moved elsewhere to avoid being caught. The food cart was technically a DIY food organizer to be attached to a scooter or any wheelers. The street food sellers reused whatever materials that they have to hold food and reserve space for “dining”. We often had bánh mì and xôi wrapped in newspapers, chewing food that might have been printed with the morning news. Street food culture created a casual service style, allowing imperfections from service designers and users/consumers. Our food and drink is contaminated by transportation dust, street lights, bugs, noise of sale promos and bargains,… immersed in the busy city life. Anyone can buy and eat the street food, but not everyone would enjoy them. Although street food attracted tourists, they might be scared of the contaminations, as their foreign stomachs could not bare to local ingredients and mixes. Their minds are probably framed with the concept of Viet Nam through the branded, industrial food such as Phở which are often served in restaurants. The locals like the service could be of many things: the location, the food, the friends we eat with, the gossip we share, our conversations with the seller, and the seller themselves. Sometimes, children helped their parents with selling the products, the old people sell random things on the pedestrian sidewalk – although passengers might not be hungry or in need of them, some would buy these anyway.

Mua ủng hộ is the common term for this case. That term means I buy these to support you, as I see you suffering. That’s the gap in our realities, so my action hopes to transcend such gap.

When there remain many social issues in a developing country, care between sellers and buyers, service designers and users, or simply human interactions take place. Less intentional design and regulations allow more space for human interactions. Although cảm ơn or xin lỗi were not common words in the street service in Viet Nam, the conversation in street service is often filled with lời chào hàng (invitations to purchase), nài nỉ ỉ ôi (beggings), mặc cả kì kèo (bargain), đôi co (argument), and mắng vốn (complaint). Mechanized sentences of politeness were not vastly used in street services but are increased in growing medium- to high-end services in entertainment and education in Hồ Chí Minh city.

Where would alienation in service design lead us to?

I’m afraid of the decrease of mua ủng hộ in the era of automation in service design. Automation includes the high use of technology for efficiency in function, and satisfaction based on polite phrases of customer service. Dialogues and emotions are often displaced by these automations to avoid fuss in service design and usage. When service is less about human interactions and more about user conflict management, it is proficient and boringly pleasant. Walking between the United States and Viet Nam, I can see the drastic gap in service design and positionality. My academic-based occupation in campus towns in the States has limited the kinds of service that I frequent with: more big brands in daily use, more digital technology, and more service and products of diverse geopolitical cultures. As a service user, I am designed to be reduce human interactions to maximize access and benefit from the service design. Focus on efficiency in service usage normalizes ignorance, otherization, and alienation of human interactions. This created numb responses among the users. Even big call-to-actions crucial to the existence of service design are not attractive o users if they are not to the benefits of users. Users are not used to human interactions in automatized service even when the service tries to talk to users who are using this service. Mua ủng hộ is no longer from a moral responsibility as it is undermined by efficiency and self-benefit caused by automation and alienation in service design.

Acknowledgements: I’m writing this blog from reading the concept alienation, systemic userism, and alter/native in decolonizing design shared by Dr. Frederick van Amstel.