Context

Guest lecture at MxD Research and Practice, taught by Dr. Frederick van Amstel, in Fall 2024.

Okay, so, thanks everyone for reading. Take your time. I’ll just share a bit, and hopefully, it will provide another perspective on what has not been shared, or what has been a context for this paper. First of all, I would like to acknowledge that yesterday was Indigenous Peoples’ Day. I also admit that I have limited knowledge on this matter, but it is an important issue as we are here in Florida, United States, as people of diverse cultures and immigrants in a land that dispossessed Indigenous people and has not provided official apologies or acknowledgments to them. This reflection also leads me to think about Vietnam, the nation where I was born and raised.

To this day, Indigenous people have played an important role in our process of gaining independence and post-war development. However, from what I have researched, the government does not officially acknowledge the existence of Indigenous people. The term ‘Indigenous people’ is replaced with ‘minority social groups’ or ‘minority ethnic studies.’ This is something I will strive to learn more about in the future. For today’s activity, I want to emphasize…

[Professor: Are you part of those Indigenous or minority communities?]

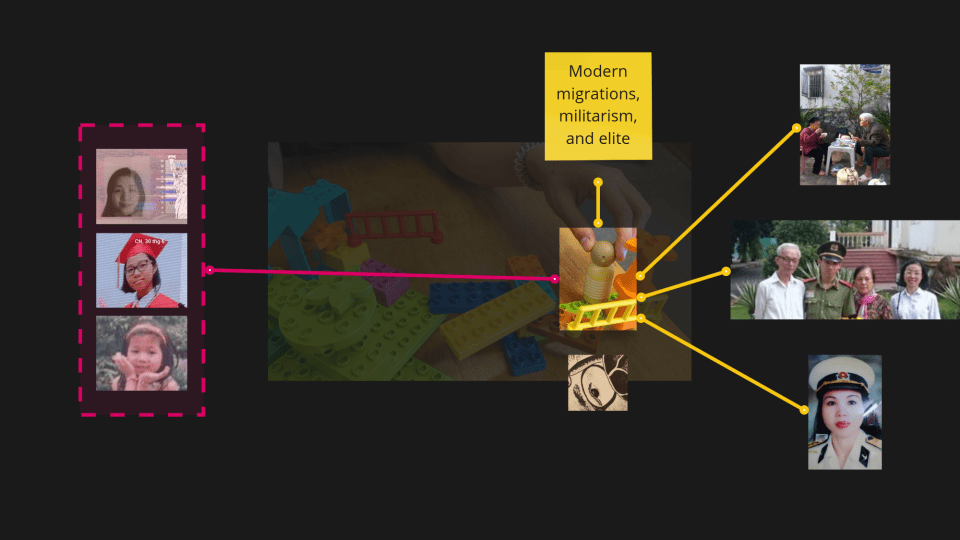

In Vietnam, there are 54 ethnicities, with 53 considered minorities. I am among the Kinh people, who are the dominant group, comprising more than 60% of the country’s population (update 2009 85.7%). [As a Kinh ethnic with family migrating to the south Vietnam from the north] I have a lot of privilege [besides disadvantages], similar to how white people have privilege in the United States, but I did not come to this realization when I was in Vietnam. I want to share more about this in my presentation.

Metaphors in identifying culturally embedded selves

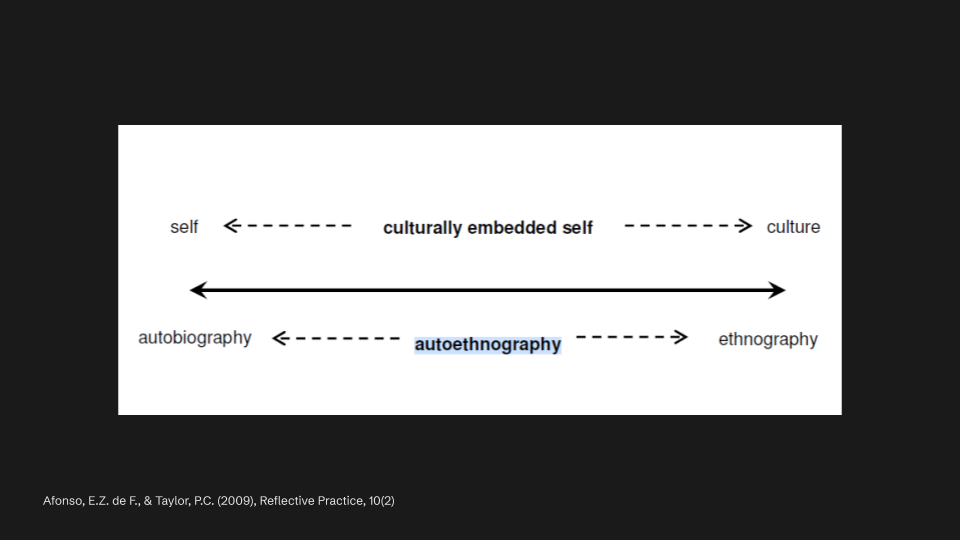

I engage with metaphors a lot in this critical process of reflecting and positioning my culturally embedded self. This involves constant dialogues with all of you, as well as with Fred and other professors. What is a culturally embedded self? It is the intersection between self and culture, a place where we reflect on ourselves as bodies that embody intertwining cultural complexities. I see the culturally embedded self not as an individualist perspective, but as one that projects the complexities of the cultures that the self has experienced. The culturally embedded self is unique, but it also acknowledges the collectives it has been part of.

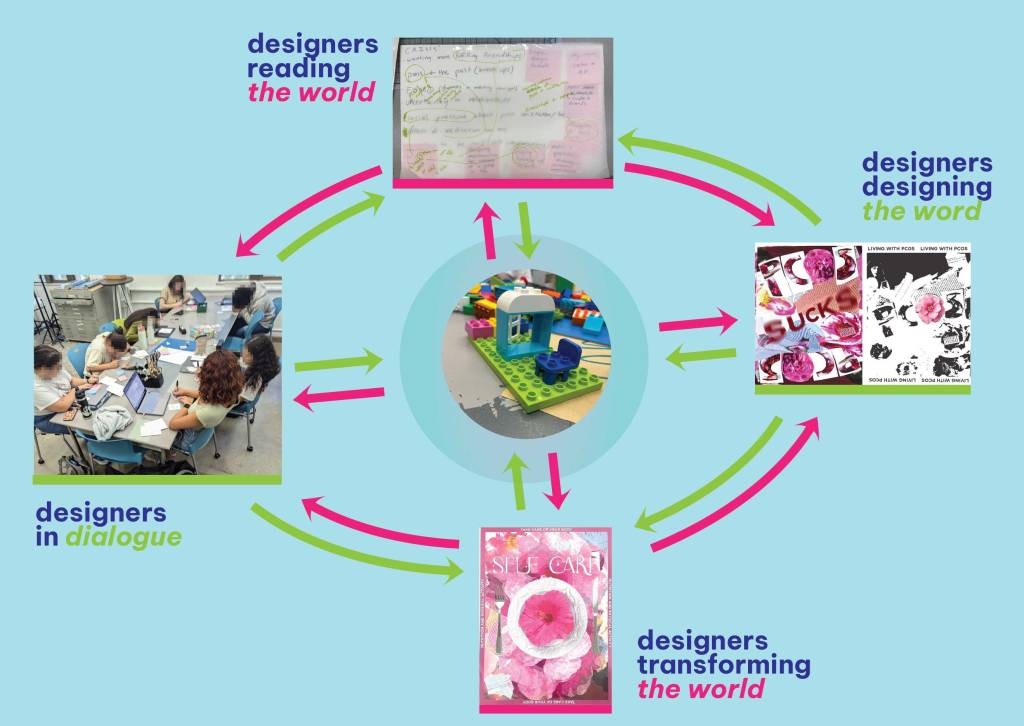

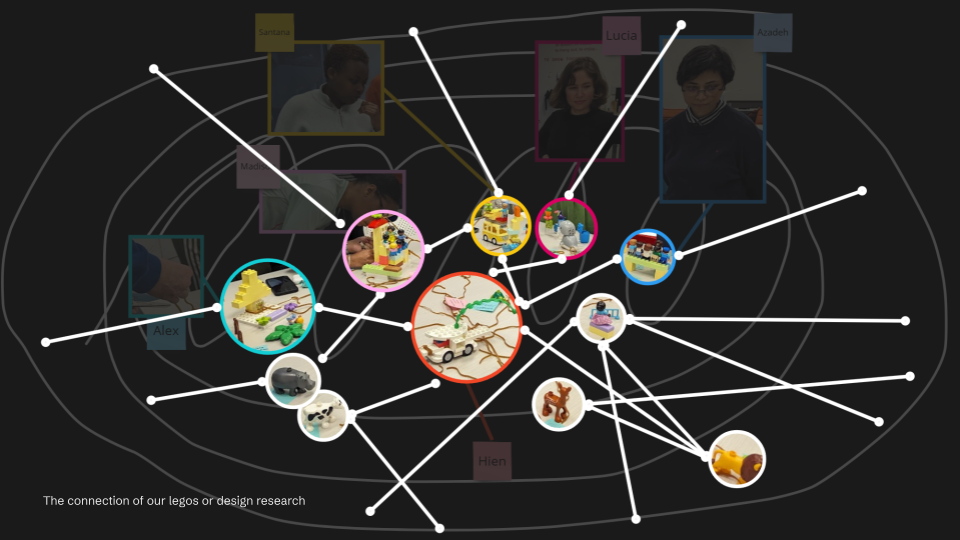

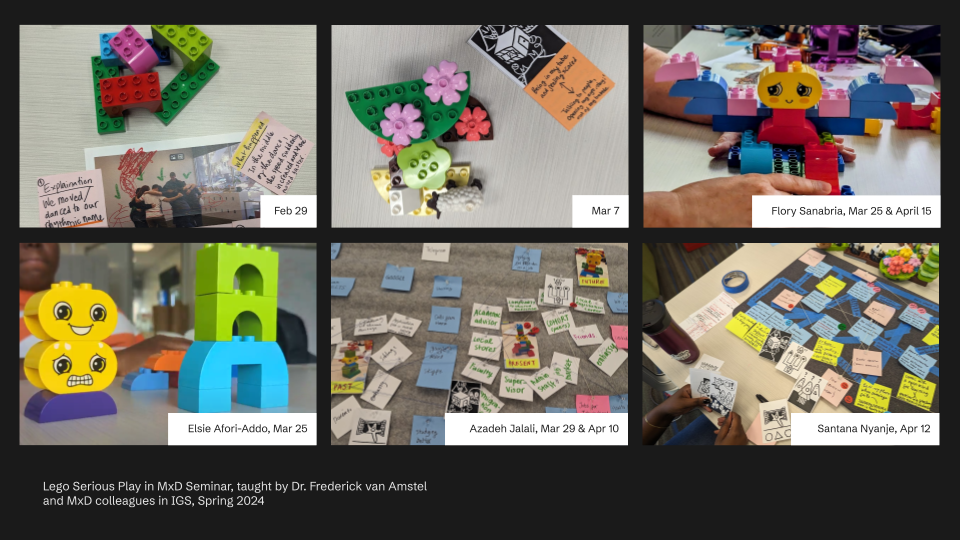

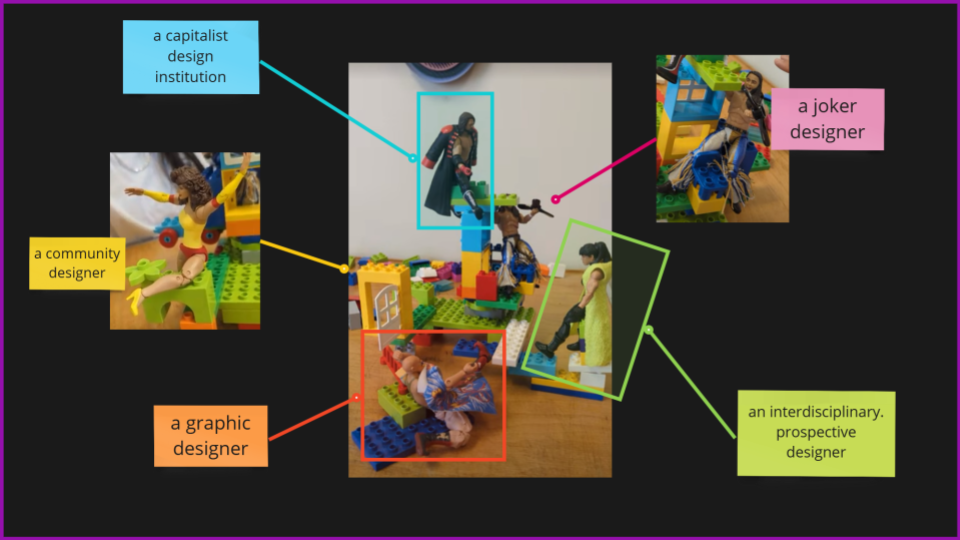

We have been using metaphors, physical metaphors, to represent our culturally embedded selves. You will see yourselves in this photo and in this presentation. We often represent ourselves through cultural metaphors, especially when you read the papers. But today, I will emphasize Legos and physical metaphors. The Legos represent our design research and the topics we focus on, crafted directly by our hands. They symbolize ourselves, but they also represent the things outside of ourselves and how they connect within the larger ecosystem maps, which we will link together using rubber bands. I’m curious how these ecosystem maps relate to your self-representation and your perception of diversity, nationality, and geopolitics, which we’ll explore today.

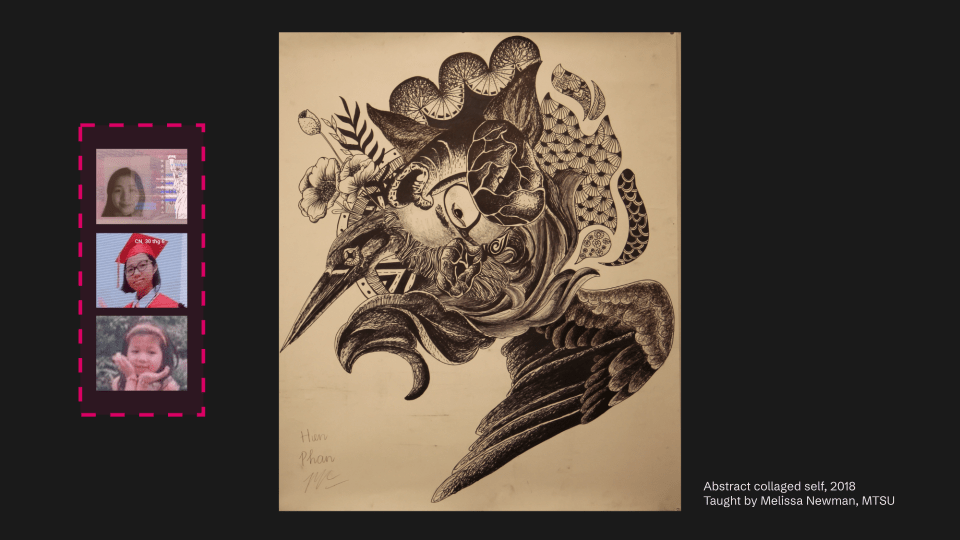

Beyond the classroom, I engage with physical metaphors like Legos and serious play in advising meetings, reflecting on my journey as an immigrant. What is that woodened doll in the chaos of systems crafted by Legos? It represents me at different stages of my life—from Vietnam to the United States, from being a citizen to becoming an immigrant. It is also a metaphor for my ancestors, grandparents, and family members, some of whom were involved in police departments and education. They embodied the institutional power of the Vietnamese government, which I perceived as a rigid structure at the time, though I did not have the language for it back then. When I came to the United States, it felt like a relief. I could explore art and design in ways that may not have been the norm in Vietnam or in my family.

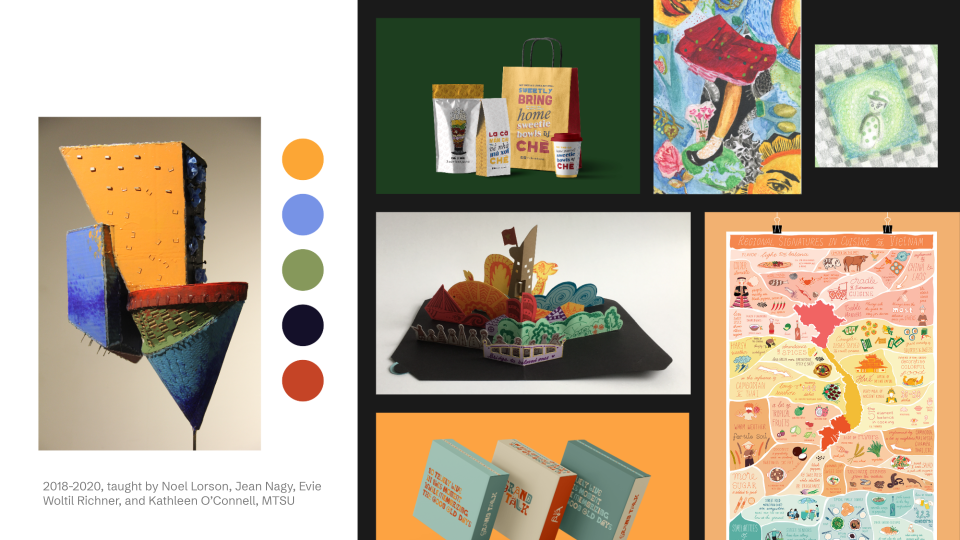

Over time, I began to notice a consistent color palette in my work. I use wings and flying objects as metaphors for liberalism, institutional embodiment, and meticulousness, expressed through low-tech materials like sculptures and paper. When it comes to digital platforms, I see this color palette in how I represent myself in relation to Vietnam, nationalities, and identities. I still like these color palettes, but I’ve started to critically consider how they may perpetuate stereotypes. These color palettes aren’t entirely personal or unique to me; they are influenced by media I consumed from Korea, Japan, and other Asian countries, as well as social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest when I missed home in the United States.

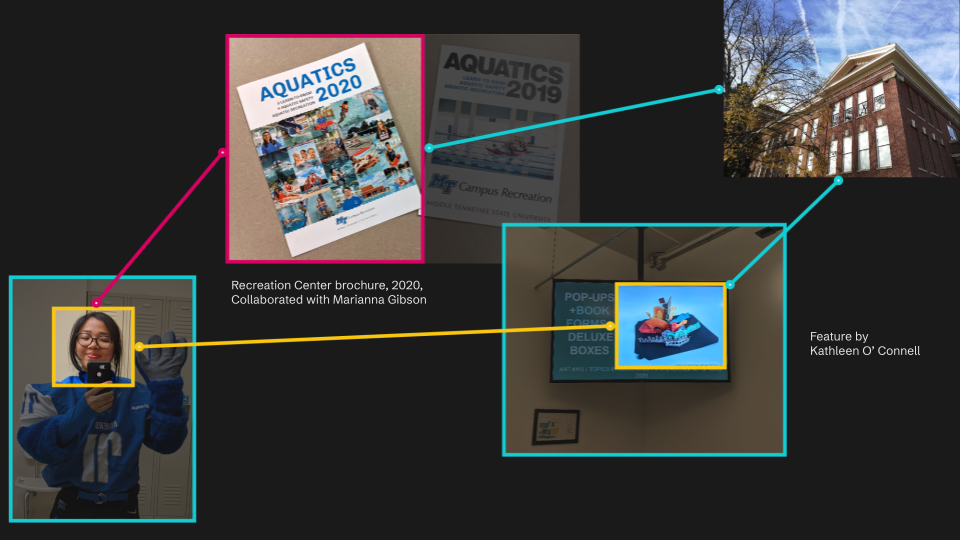

I engaged in these activities while positioned at a predominantly white university in Murfreesboro, a small campus town in Tennessee. Gradually, as you can see through the papers, I sought more self-representation through roles like graphic design student and diversity manager. I saw myself aligning with institutional success, embodying pride in family and nation within the predominantly white university. Of course, I was happy because that brought a sense of inclusivity and success, didn’t it?

Why are there conflicts within the tokens of diversity in the multicultural education?

But during this long trajectory, there has been a very important figure that I have not yet mentioned—Ha, my best friend, the first Vietnamese person I met in the United States. She has different political viewpoints from me, which I didn’t even realize I had at the time. Through our conversations, she educated me a lot about the other side of Vietnamese culture and politics that I was unfamiliar with. Her existence connects to populations that have been dehumanized in Vietnamese literature and history—namely, Vietnamese refugees in the United States and other global North countries.

Our conversations were full of passion and anger. I often wondered, “Why are you so much more Vietnamese than me?” Despite both of us being raised in Vietnam, why did she seem to have more passion and knowledge about our country? This contrast made me rethink my direction. I began to move away from the commercial design work I was once so proud of, shifting my focus toward critical social studies, refugee and Asian American communities, and community-based design. This became the trajectory of my graduate program.

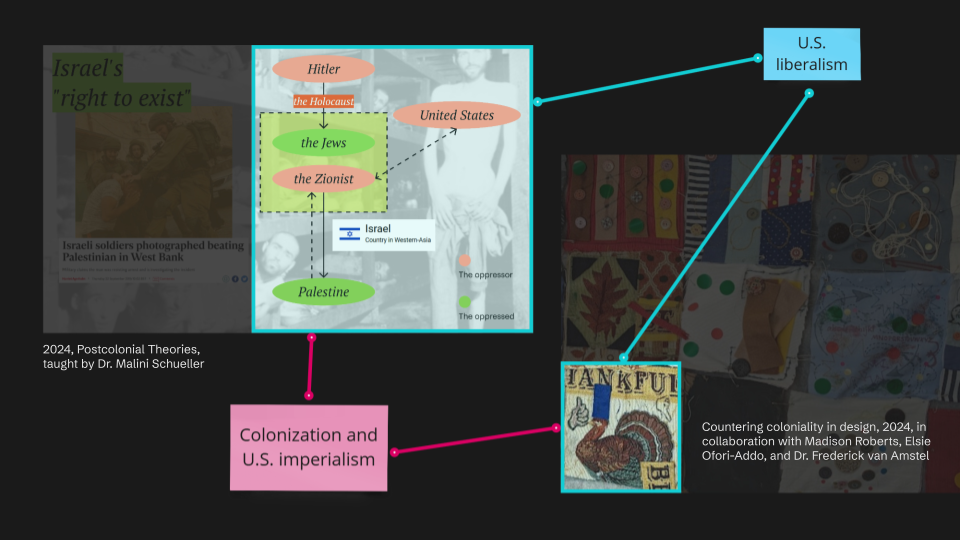

As I engaged with the conflicts among Vietnamese people, often seen as tokens of diversity and multicultural education, I started questioning why these divisions existed. I took a class, which you may have seen referenced here and there, with Dr. Malini Schueller on Asian American refugees and aliens. In this class, I began to understand the literature surrounding Vietnamese refugees and to analyze it with new perspectives. I observed common patterns, such as the portrayal of violence against Vietnamese people, the American dream of modernity, and the normalization of alienation as part of the Asian American model minority stereotype in the United States.

As I delved deeper, I focused on the flag of the old Southern Vietnamese government, which existed before the current Vietnam. This flag was absent from the history textbooks I grew up with, as it was considered anti-patriotic and anti-nationalist in Vietnam. It was an enemy to the flag that I, as a modern-day Vietnamese, wore with pride—a red flag with a yellow star in the middle. The Southern Vietnamese flag, with its three stripes, was even absent during our [college] graduation ceremonies [in the United States].

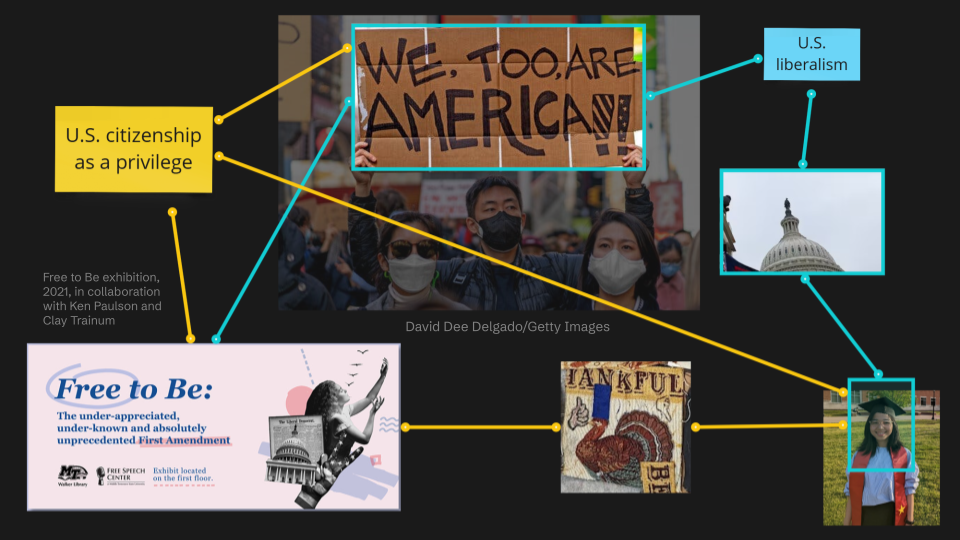

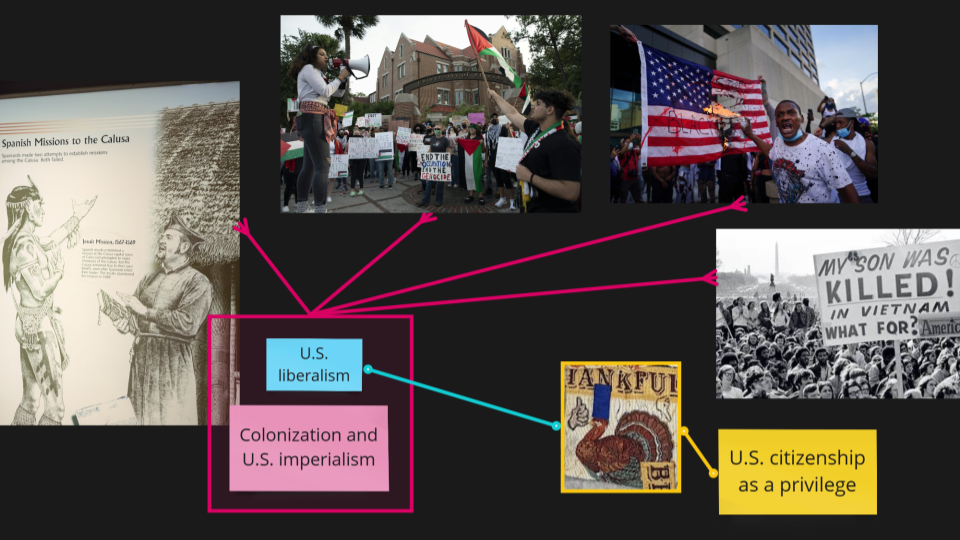

I began to see that this Southern Vietnamese flag appeared in the United States’ political context, most notably during the January 6 Capitol attack encouraged by Donald Trump over disputes concerning the 2020 election results. I started piecing together how this flag, symbolizing Southern Vietnamese governance, was linked to United States liberalism, the “Make America Great Again” movement, and the resistance to communism. So, I dug deeper.

This was during 2020, a time when the United States was in the throes of a presidential election, the COVID-19 pandemic, and intensified foreign relations with China. Anti-Asian sentiment spiked, with terms like “Kung flu” being used. Meanwhile, there was a significant “Stop Asian Hate” protest, not just by Asian Americans but by various minority social groups. In the context of all this turmoil, I began to see United States citizenship as a privilege. I asked myself, “Why is this citizenship so important? Why do I feel the urge to be grateful for it, and how does it connect to the Constitution and the institution where I study?” I wondered why I continued to wear the flag of a communist country, even in this environment.

As I dug deeper, I began to understand that United States liberalism is closely linked to United States imperialism—the notion that the U.S. is the global dominant power, justified in intervening in the geopolitics of other nations. This intervention often comes under the guise of “helping,” as seen in the struggles between Israel and Palestine, where the U.S. has supported Israel’s establishment as a nation-state, leading to ongoing violence and genocide against Palestinians. This realization made me question whether I still needed to be grateful for United States citizenship and education. It created a personal crisis.

I started connecting the dots—U.S. exceptionalism isn’t limited to foreign affairs but extends to the lands it occupies, where the dispossession of Indigenous people continues. This is evident in the attacks on student protests at the University of Florida, which occurred besides the “Stop Asian Hate” protests in 2020, as well as the “Black Lives Matter” protests, which included the burning of the American flag—a flag I once saw as a symbol of privilege. That flag is also a representation of a nation that has attacked Vietnam, specifically the Northern Vietnamese regime of which my brother and ancestors were a part. Now, I find myself in the U.S., aligned in some ways with the Southern Vietnamese regime, opposed to the Northern one. So, do I still feel grateful?

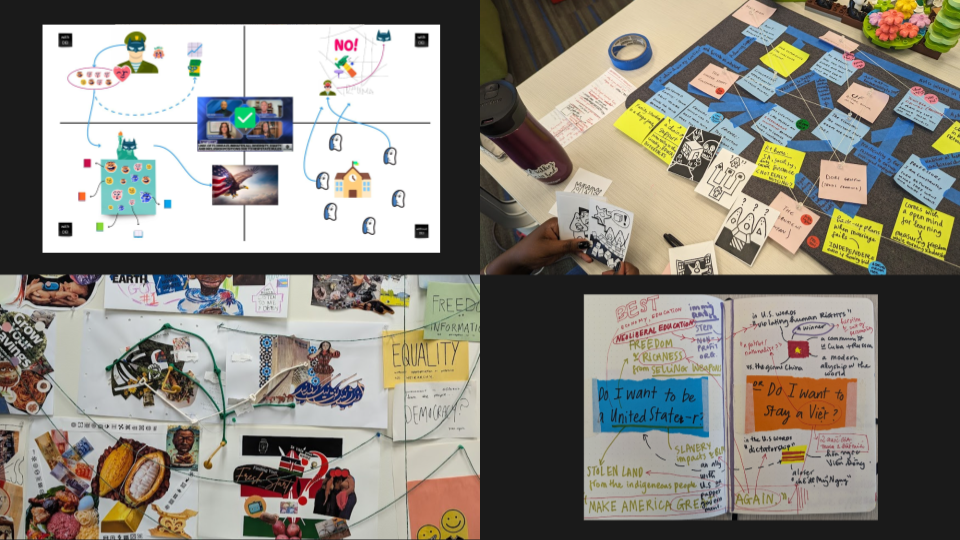

These reflections have led me to see myself, and others, as part of a diverse existence within the institution. But this diversity is different from institutionalized diversity, which categorizes people by nationality, geopolitics, capitalism, and community, or from individualized diversity, like being labeled as Vietnamese American or Asian American. In the local context of the University of Florida, where policies are becoming increasingly capitalist, racist, and neoliberal, I see diversity differently.

I use icons to understand the complexities of Florida’s policies, where student protests are silenced and people from minority groups—including socialists, communists, LGBTQ+ communities, Indigenous people, and citizens of the seven “countries of concern” like Iran, Russia, and Venezuela—face significant restrictions in academic research. The box we are in, striving for the future of super-development with generative AI and promising job prospects, also turns natural resources into tourism and golf courses. Yet, are we still grateful for that?

These experiences make me question the complexities of diversity within this institution, and by extension, within the United States’ multicultural education system. What other ways are there to understand U.S. citizenship besides as a privilege? What can we do as postcolonial, global citizens? These questions drive my research and guide my thesis.

What can I co-design with others as post-colonial global citizens?

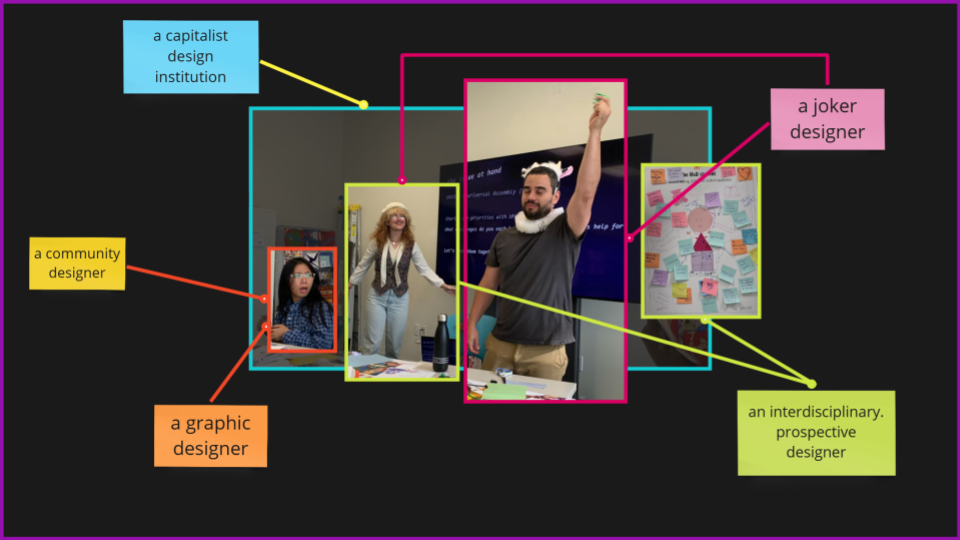

During this process, I engaged and reflected on what we have been doing so far in this space. This is a space where we reflect on ourselves as pluriversal selves, engage in conversations with others, and unpack the complexities of policies through icons and metaphors. You are all invited to be part of this process. It has been a very meaningful journey so far—both reflexive and critical.

We use metaphors extensively—through physical metaphors like Lego serious play, as well as through deck cards and toolkits—to position ourselves as complex beings within complex systems. Through these metaphors, we are not only redesigning but also reproducing them. This involves receiving cultures as they are, with their associated stereotypes, while simultaneously reproducing cultures in ways that reflect our individual and collective perspectives. Yet, these reproductions can sometimes perpetuate stereotypes, which necessitates ongoing reflection and careful annotation over time.

One research question that arises here is: how does diversity by design manifest in the state of Florida, with its neoliberal and racist policies? I engage with Lego serious play beyond individual stories and identities, focusing instead on the structures we inhabit. Within the studio, we are multiple designers of various expertise—graphic designers with cultural interests, prospective designers, community designers. Despite our best efforts, we still find ourselves within a capitalist design institution.

This has led to the emergence of a new role, which I call the “Joker designer.” This role became clearer to me during one of the experiments with Cassie, hosted by Cassie and Narayan, involving a string exercise. I was surprised by my own reactions—expressions I hadn’t anticipated. It made me realize that, as a graphic and community designer, I tend to shy away from conflicts. When politics come up, I often try to avoid them. However, there is a need to confront conflicts and actively intervene in these cultural contexts.

The challenge lies in engaging with troubles, not to perpetuate them, but to examine them critically and to explore multiple ways in which they can be approached from different perspectives. In this space, we can still pursue our individual interests, but we must also be mindful of the power dynamics we embody and manifest in our practices, both within and outside of this space. This is especially important when working with local community members and reproducing cultures, which can inadvertently lead to the perpetuation of stereotypes.

How can we, “diverse designers”, critically position our culturally embedded selves from the diversity by design?

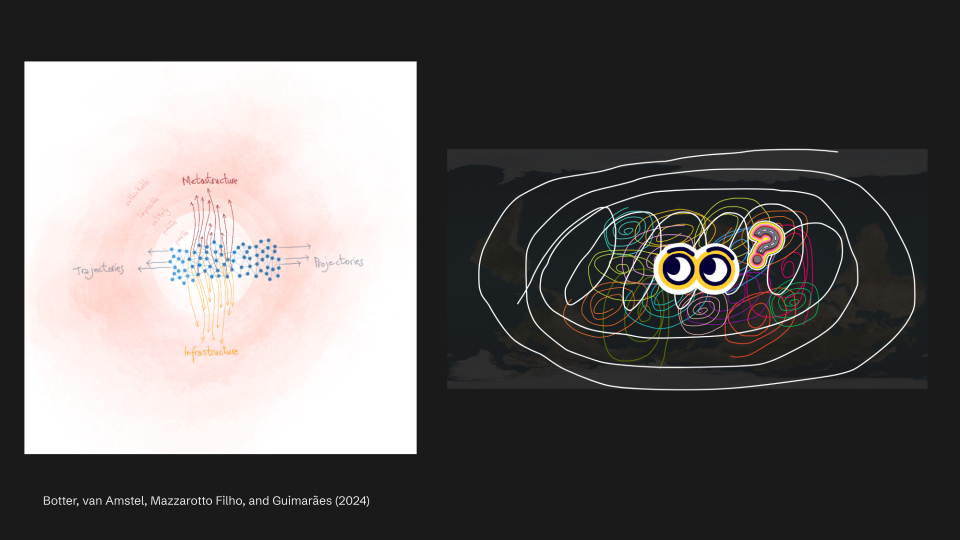

So, who are we in this space, and how can we critically position ourselves within it? There is a lot to reflect on, and it requires us to constantly look back, patch the pieces together, and understand the broader picture. This is my constant mode—always spiraling, always revisiting these ideas. But I’m reminded to stay with this mode, rather than chasing pure happiness, because I know that I am not spiraling alone. We are all here, connected. I haven’t mentioned all the people who have impacted me—my students, professors, my mom—but our spirals are indeed intertwined. The fact that you are connected to the paper I co-wrote with Fred is proof of this interconnectedness.

The troubles are around us, within us, and they connect us. How can we engage in conversations about geopolitics and culture that go beyond celebration? How can we embrace more conflict and critical reflection, seeing ourselves not just as oppressed or marginalized, but also as reproducers of oppression? These are the complexities that I am still grappling with, but perhaps you can help me navigate them.

Today’s activity will be about geopolitics, about what designers can do in that space, and about thinking beyond the norms and stereotypes, venturing into impossibilities and exploring the unconventional. This is the direction I am driving my practice towards.

References:

- Angelon, R., & van Amstel, F. (2021). Monster aesthetics as an expression of decolonizing the design body. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 20(1), 83-102.

- Botter, F., van Amstel, F. M. C., Mazzarotto Filho, M., and Guimarães, C. (2024) Prospective design: A structuralist design aesthetic founded on relational qualities, in Gray, C., Hekkert, P., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P. (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.883

- Freire, P. (1985). Reading the world and reading the word: An interview with Paulo Freire. Language arts, 62(1), 15-21.

- Haider, A. (2018). Mistaken identity: Race and class in the age of Trump (Vol. 24). London: Verso.

- Said, E. W. (1977). Orientalism. The Georgia Review, 31(1), 162-206.

- Schueller, M. J. (2009). Locating race: Global sites of post-colonial citizenship. State University of New York Press.

- Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2015) Expansive design: designing with contradictions. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789462331846

- —- (2024, August 28). Reading the world with Lego Serious Play. Retrieved from Frederick van Amstel website: https://fredvanamstel.com/talks/reading-the-world-with-lego-serious-play

- —- (2015, November 20). Representing contradictions without trying to solve them. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from Frederick van Amstel website: https://fredvanamstel.com/blog/representing-contradictions-without-trying-to-solve-them

- —- (2021, January 27). Visual oxymoron. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from Frederick van Amstel website: https://fredvanamstel.com/tools/visual-oxymoron

- —- (2020, April 21). What is a contradiction and why it is relevant to design research? Retrieved October 7, 2024, from Frederick van Amstel website: https://fredvanamstel.com/blog/what-is-a-contradiction-and-why-it-is-relevant-to-design-research